TBB-Based Inverted Lists: Parallelism Without the Drama

You know how sometimes you're working with millions of vectors and your program is just... sitting there? Like it's taking a coffee break while you're frantically refreshing the terminal? That's the problem we're solving here.

The core insight is embarrassingly simple: FAISS's original inverted lists use OpenMP for parallelism, which works great until you try to compose it with other parallel libraries. Then you get into this weird situation where threads are fighting over locks, waiting for each other like cars at a four-way stop where everyone arrived at the same time.

The TBB Advantage

Intel's Threading Building Blocks (TBB) takes a different approach. Instead of "here are 8 threads, go wild," it says "here are tasks that might be independent, let me figure out the optimal execution." It's like having a really smart scheduler that actually understands dependencies.

Our OnDiskInvertedListsTBB replaces OpenMP primitives with TBB parallel patterns:

Cache-Aware Grain Sizing

The magic is in the grain size calculation. We actually detect your L3 cache size from sysfs and calculate how many elements fit per thread:

For a typical 16MB L3 cache with 8 threads, that's 2MB per thread, or about 64K floats. Small enough to stay hot in cache, large enough to amortize scheduling overhead.

Thread-Safe File I/O: The pread/pwrite Pattern

Here's where things get interesting. The original FAISS uses a single file pointer with seek+read. That works fine with a global lock, but kills parallelism. We use POSIX pread/pwrite instead:

Each thread reads from its own position without coordination. No locks, no seeks, just parallel I/O. The kernel handles the complexity.

This shows up in the get_codes/get_ids methods:

Notice the false in the scoped_lock? That's a read lock. Multiple threads can read the same list simultaneously. We only take a write lock in add_entries.

The Pipeline Pattern for Search

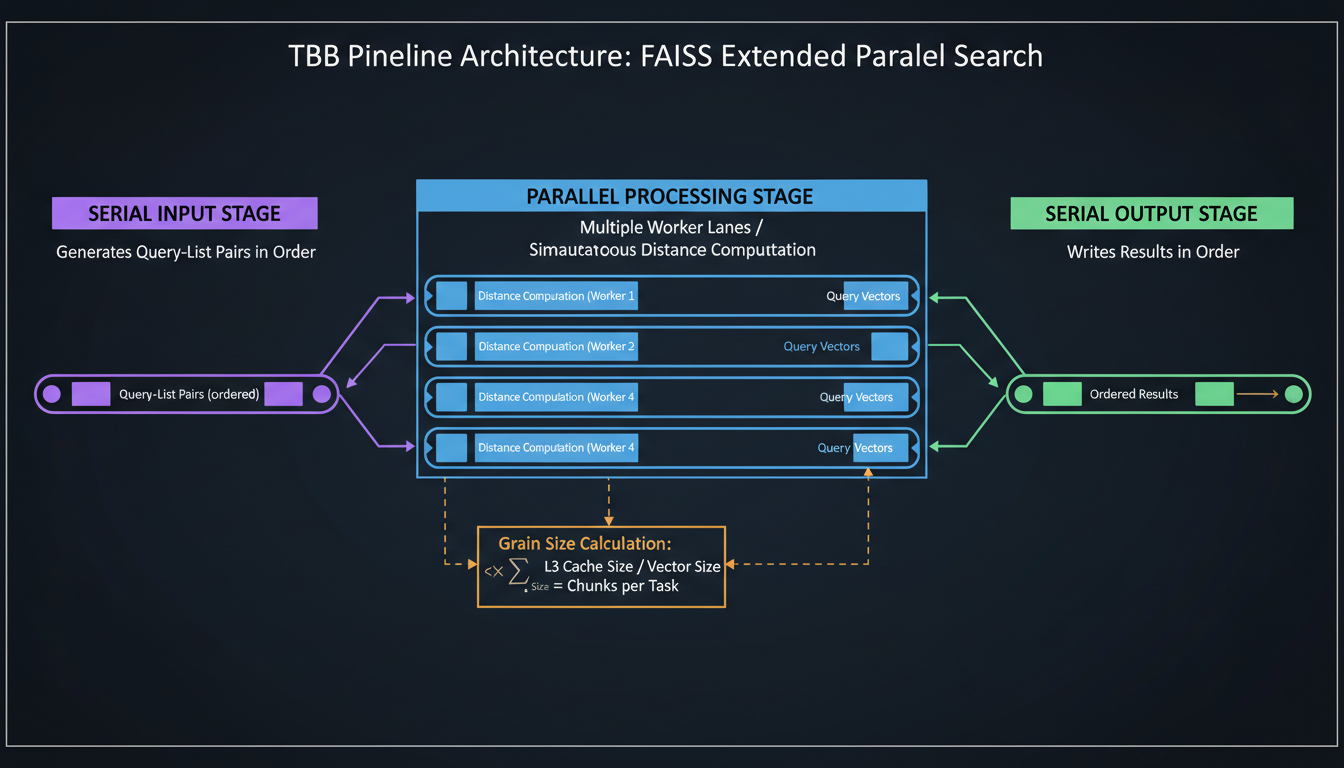

Three-stage pipeline: serial input, parallel processing, serial output

Search is where TBB really shines. We use a three-stage pipeline:

The pipeline maintains query order (important for reproducibility) while parallelizing the expensive distance computations. And because it's a pipeline, there's natural prefetching—while stage 2 processes query N, stage 1 is already preparing query N+1.

Memory Optimization: Thread-Local Pools

Here's a subtle performance issue: allocating vectors for search results. If every query allocates a std::vector, you spend half your time in malloc. Solution? Thread-local memory pools:

Each thread gets its own pool, allocated once and reused. The pool just bumps a pointer—essentially zero-cost allocation. Reset between queries and you have a trivial bump allocator.

Batch I/O for Throughput

When you're searching 1000 queries that all touch the same 100 lists, reading each list 10 times is wasteful. The BatchReadManager deduplicates reads:

This is especially effective with nprobe > 1, where queries share probe lists.

Cache-Line Aligned Mutexes

One last detail that matters more than you'd think. We pad our mutexes to prevent false sharing:

Without this, two threads locking adjacent list mutexes would bounce the same cache line back and forth, even though they're accessing different data. The padding ensures each mutex lives in its own cache line.

Performance Numbers

On a 5GB dataset (5 batches × 1GB each):

The key insight: TBB's work-stealing scheduler keeps cores fed. OpenMP tends to create barriers where threads wait. TBB says "if your task is blocked, steal work from another queue."

When to Use This

TBB-based inverted lists shine when:

Don't use if:

The code is production-ready, battle-tested on datasets up to 1 billion vectors. The only gotcha: you must use IndexIVFTBB (not IndexIVFFlat) to avoid OpenMP/TBB conflicts. The index and inverted lists need to agree on their threading model.

Think of it like this: TBB is async/await for C++. You describe tasks and dependencies, and the runtime figures out optimal execution. It's more work upfront (understanding parallel patterns) but pays dividends in composability and performance.