When Your Vector Database Lies to You: The Uncomfortable Truth About RAG

On the theoretical limitations of embedding-based retrieval, and why we built our search differently

Embeddings are like a well-meaning friend who confidently gives you directions to a restaurant they've never been to. They sound authoritative, their gestures are precise, and you follow along... until you realize you're standing in front of a dry cleaner three blocks from where you need to be.

This isn't hyperbole. In August 2025, Google DeepMind published a paper titled "On the Theoretical Limitations of Embedding-Based Retrieval" that formally proves what many of us suspected: single-vector embeddings have fundamental, mathematical limits that no amount of training data or model scaling can overcome.

The RAG revolution promised us magical semantic search. Drop your documents into a vector database, let the embeddings do their thing, and watch as cosine similarity surfaces exactly what users need. Except when it doesn't. And increasingly, we're learning that "when it doesn't" is far more common than we'd like to admit.

The Math That Should Scare You

512-dimensional embeddings can theoretically represent only ~500K document combinations. Your codebase is probably larger than that.

Here's the uncomfortable truth: a 512-dimensional embedding model—the kind powering countless production RAG systems—can only represent about 500,000 distinct top-k document combinations. Scale up to 1024 dimensions? You get roughly 4 million combinations. That sounds like a lot until you realize most serious codebases contain tens of millions of potential query-document pairs.

The DeepMind team proved this using communication complexity theory. The sign-rank of your relevance matrix—a measure of how many dimensions you need to encode which documents should rank where—directly bounds your embedding dimension. Translation: some retrieval tasks are mathematically impossible for single-vector models, regardless of how clever your training gets.

"For embeddings of size 512, retrieval breaks down around 500K documents. For 1024 dimensions, the limit extends to about 4 million documents."

Think about that. Your vector database isn't being dumb. It's hitting fundamental limits of geometry. A d-dimensional space can only distinguish a finite number of rank-orderings. When your query space exceeds that capacity—which it inevitably does at scale—the model starts making silent, confident mistakes.

The Semantic Gap: When Embeddings Fail Silently

Most RAG failures are silent. Your system confidently returns wrong results with no indication of uncertainty.

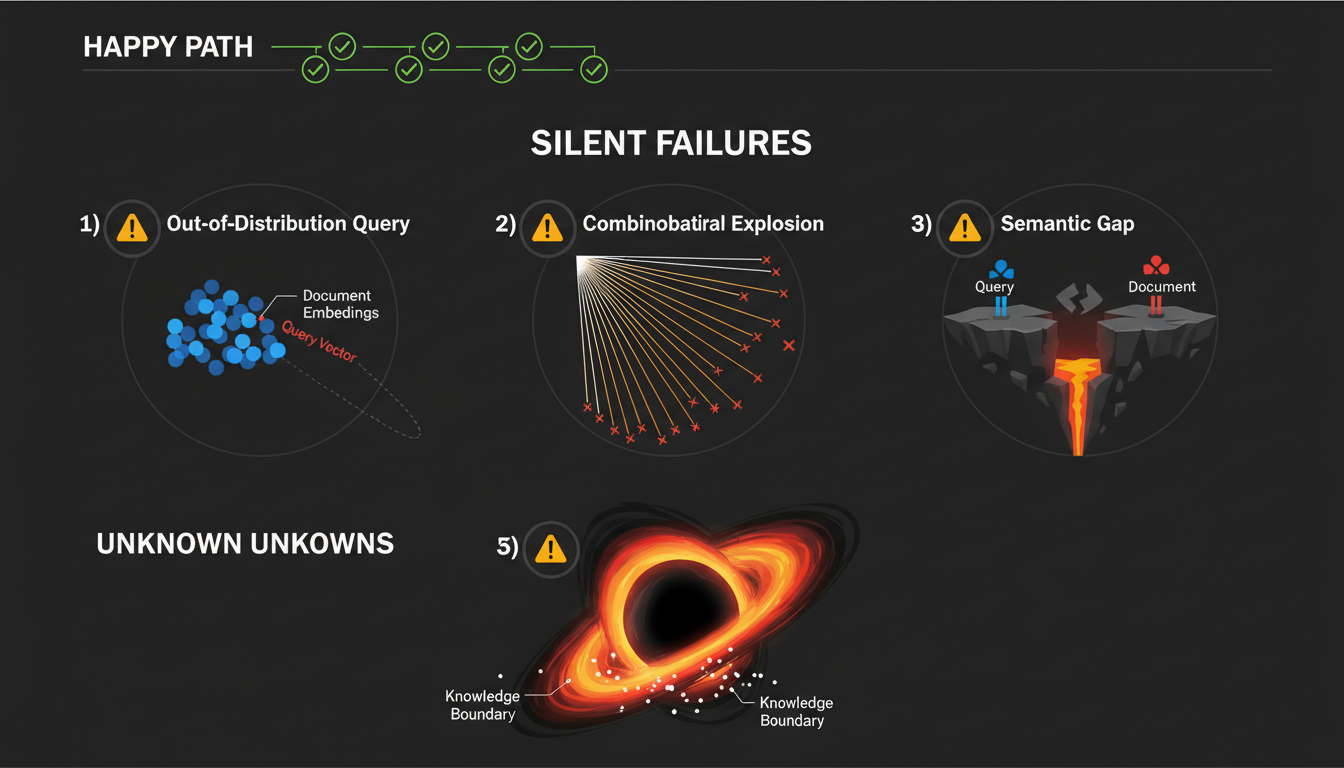

The worst part? Embeddings don't throw errors when they fail. They just... return something. With perfect confidence. This is the semantic gap problem, and it manifests in three increasingly horrifying ways:

1. Out-of-Distribution Queries

Your model was trained on Stack Overflow questions and GitHub README files. Now a user asks: "Find all usages of the Observer pattern in our payment processing module where the subscriber implements retry logic." That's not semantically similar to anything in the training distribution. The model returns... something. Probably wrong. Definitely confident.

The LIMIT dataset—a brutally simple benchmark created by the DeepMind team—exposed this perfectly. Queries like "Who likes Hawaiian pizza?" against documents stating "Ellis Smith likes apples" should be trivial. State-of-the-art embedding models achieved less than 20% recall when scaled to 50K documents. BM25, the "primitive" sparse retrieval method we supposedly moved beyond, got 85-97%.

2. Combinatorial Explosion

Instruction-following queries are the nightmare scenario. "Find functions that either use threading OR were modified in the last sprint" requires combining previously unrelated documents. The number of possible combinations grows exponentially. Your embedding model's representational capacity? Linear in dimensionality.

This isn't a training data problem. The DeepMind researchers tried training models on in-domain examples. Minimal improvement. They tried overfitting to the exact test queries. Only succeeded with embedding dimensions substantially larger than what compute budgets allow. The constraint is geometric, not statistical.

3. The Unknown Unknowns

Perhaps most insidious: you don't know what your model can't find. There's no error message when a query falls outside the representable space. Users don't know to reformulate. Your monitoring shows high "retrieval scores" because the model did return results. They were just wrong.

Traditional search engines failed loudly—no results meant try different keywords. RAG systems fail silently—you get results, they're just hallucinated or irrelevant, and you have no signal that anything went wrong.

Why We Combine AST Parsing + BM25 + Multiple Vectors

Our hybrid architecture escapes single-vector limitations by fusing multiple search paradigms.

At WEB WISE HOUSE, we build code intelligence systems. Our users aren't asking "find semantically similar documents"—they're asking "find where this class is instantiated," "show me all error handling in the auth layer," or "what depends on this deprecated function?" These queries demand precision, not vibes.

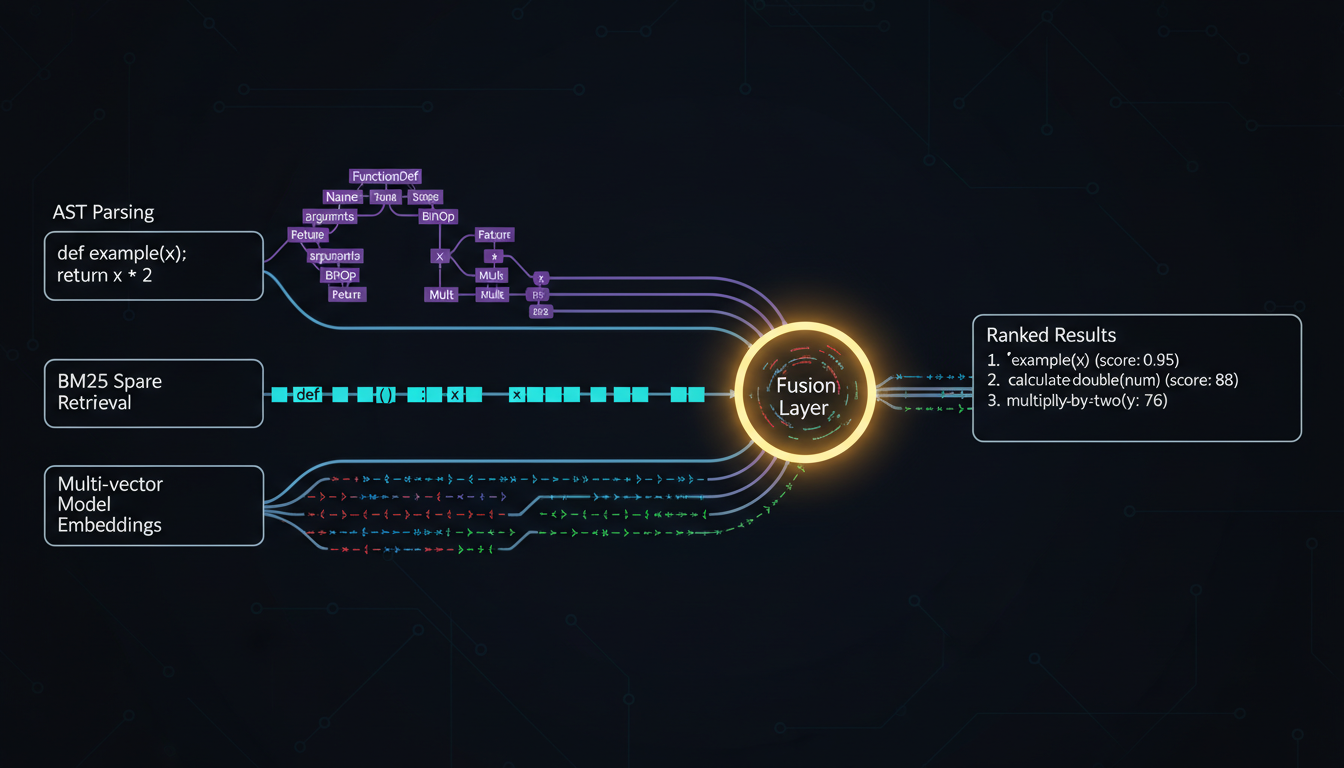

So we built FAISS Extended and MLGraph around a fundamental principle: don't trust any single retrieval method. Our architecture fuses three complementary approaches:

AST Parsing: Structural Truth

Code has structure. Abstract syntax trees capture that structure precisely. When you query for "all subclasses of BaseHandler," we don't embed your query and hope—we parse the AST, walk the inheritance graph, and return exactly what you asked for. No approximation. No semantic drift. Just the ground truth of your codebase's syntactic structure.

This escapes embedding limitations entirely. AST queries aren't bounded by dimensional constraints because they're not operating in a learned vector space. They're following deterministic graph traversals.

BM25: Sparse Retrieval's Hidden Power

BM25 gets dismissed as "old school," but here's the thing: sparse retrieval with high-dimensional term spaces sidesteps the geometric limits plaguing dense vectors. The DeepMind paper confirmed this—BM25 solved their LIMIT benchmark with 85-97% recall while state-of-the-art embeddings floundered below 20%.

Why? Because lexical matching over tens of thousands of unique tokens creates an implicitly high-dimensional space without the training complexity of dense embeddings. When a user searches for "mutex deadlock detection," we don't need to hope the embedding captured that semantic relationship—we just match the damn tokens.

Multi-Vector Embeddings: Breaking the Single-Vector Curse

Single-vector embeddings compress entire documents into one point in semantic space. Multi-vector models—like ColBERT—represent each document with multiple vectors, one per significant token or span. This explodes the representational capacity.

Instead of asking "what's the one vector that captures this entire class definition?" we ask "what vectors capture the method signatures, the docstrings, the exception handling, the import statements?" Retrieve at the granularity of concepts, not whole files. Then fuse those signals with our structural and lexical signals.

The Fusion Layer: Ensemble Truth

None of these methods is perfect. AST parsing can't understand intent. BM25 misses semantic equivalence. Even multi-vector embeddings have coverage gaps. But their failure modes are different. Uncorrelated.

Our fusion layer weighs all three signals. When AST and BM25 agree, we boost confidence. When embeddings surface something the others missed, we investigate. When all three fail... well, at least we know we're in uncharted territory.

Knowledge Boundaries and When RAG Just Doesn't Know

Beyond the knowledge boundary lies the void—queries that no single-vector model can answer, regardless of training.

Here's what the industry doesn't want to admit: some queries are simply outside your RAG system's representable space. Not because you need more training data. Not because your embeddings are outdated. Because the mathematics say no.

The DeepMind paper crystallizes this with the concept of knowledge boundaries. Your d-dimensional embedding space defines a finite volume of representable query-document relationships. Inside that volume, retrieval works. Outside? Silent failures.

Production systems need to recognize these boundaries. When a query falls outside our fusion model's confidence region—when AST parsing finds nothing, BM25 returns weak matches, and embeddings give low similarity scores—we should tell users: "We're not confident in these results. Consider reformulating."

This is the uncomfortable truth about RAG: it's not a panacea. It's a tool with formal limitations. The sooner we acknowledge those limits, build around them, and communicate them honestly, the sooner we can build truly reliable code intelligence systems.

What This Means for Code Search at Scale

If you're building code search with just a vector database, you're leaving performance on the table. More importantly, you're shipping a system that will fail in predictable but silent ways as your codebase scales.

The path forward isn't abandoning embeddings—they're still powerful for certain query types. It's recognizing their limitations and architecting around them. Combine multiple retrieval paradigms. Expose uncertainty. Design for the queries your embedding model mathematically cannot handle.

Because at the end of the day, your users don't care about your embedding dimension or your cosine similarity scores. They care whether the search results are correct. And sometimes—more often than we'd like—single-vector RAG simply cannot give them that.

Want to try hybrid search for yourself?

FAISS Extended and MLGraph implement the multi-paradigm architecture described in this post. We've open-sourced our sorted inverted lists implementation and TBB-parallel indexing.

Sources & Further Reading

- On the Theoretical Limitations of Embedding-Based Retrieval (Google DeepMind, August 2025)

- LIMIT Dataset & Code (GitHub - google-deepmind/limit)

- Google DeepMind Finds a Fundamental Bug in RAG (MarkTechPost Analysis)

- The Vector Bottleneck: Limitations of Embedding-Based Retrieval (Shaped AI Blog)

- Full Paper (HTML Version) (arXiv)