Training at 4-Bit: The Research That Broke the Rules

Or: How We Learned That Everything We Knew About Precision Was Wrong

"Training in FP4 is like learning to paint with a limited palette—you'd think you need all the colors, but Vermeer made masterpieces with just a few."

The Dogma of Precision

For decades, we knew one thing for certain: training neural networks requires high precision. FP32 for older models, FP16 or BF16 for modern ones. Drop below that and the gradients explode, vanish, or just refuse to converge. The math was clear. The experimental evidence was overwhelming. Everyone agreed.

Then NVIDIA trained a 12B parameter model on 10 trillion tokens at 4-bit precision. And it worked.

Not "kinda worked with major accuracy loss." Not "worked for toy problems." It matched BF16 baseline performance on downstream tasks. The longest publicly documented FP4 training run in history. We were all wrong, and the hardware folks knew it.

Why This Matters for Our SLM Ensemble

We're training 7 specialized models (4B-8B parameters each) on 100B-200B tokens each. That's roughly 1 trillion tokens total across all models. FP4 training means:

- ~50% training cost reduction (2x throughput on B200)

- Train entire ensemble on single B200 (192GB → 32GB memory)

- Faster iteration cycles for experimentation

Note: NVFP4 training requires B200 (SM 100). Our GB10/DGX Spark (SM 121) and RTX 5090 (SM 120) don't support NVFP4/MXFP8 training in Transformer Engine yet. We use BF16 on local hardware, NVFP4 on rented B200s.

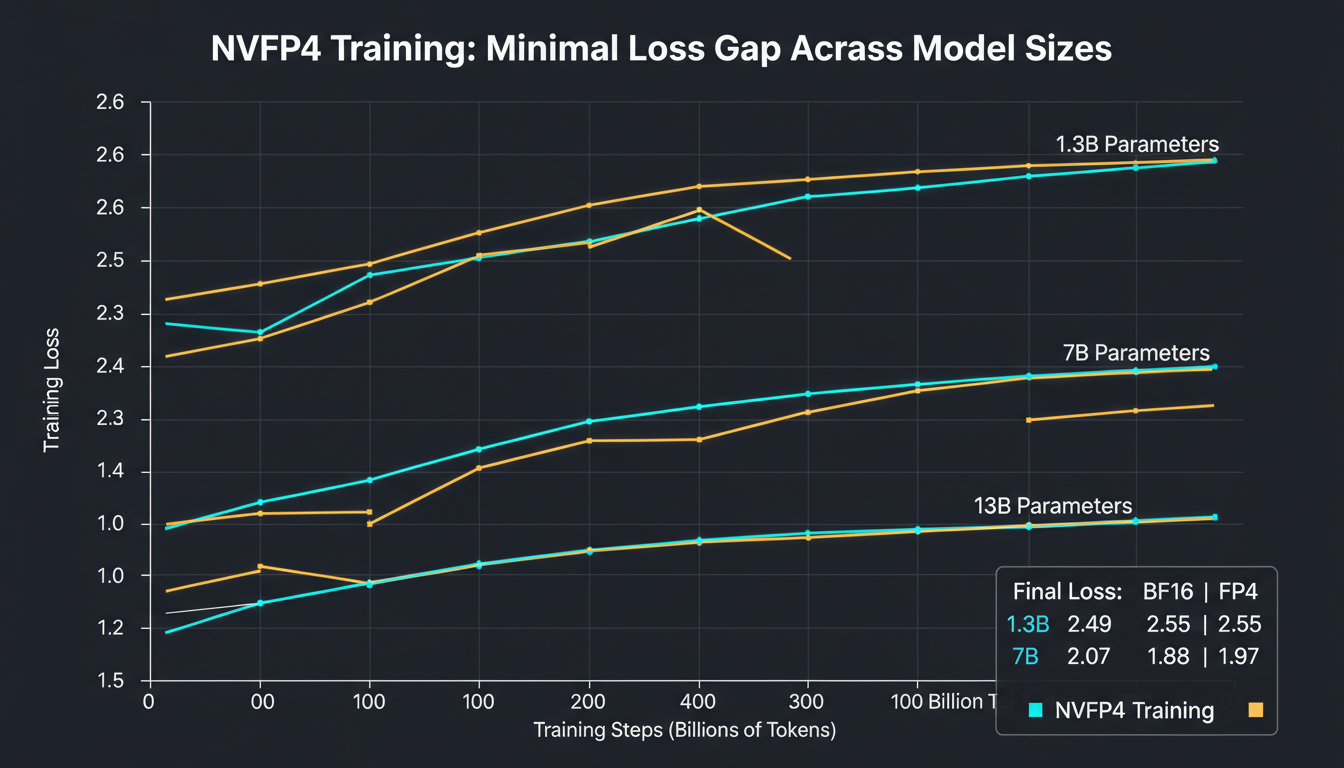

1. The LLaMA Results: Minimal Gap, Maximum Potential

NVIDIA trained LLaMA models at 1.3B, 7B, and 13B parameters for 100B tokens each, comparing BF16 baseline to FP4. Here's what happened:

| Model Size | BF16 Loss | FP4 Loss | Delta |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.3B params | 2.49 | 2.55 | +0.06 |

| 7B params | 2.07 | 2.17 | +0.10 |

| 13B params | 1.88 | 1.97 | +0.09 |

Look at those deltas. 0.06 to 0.10 loss increase. That's not a catastrophic degradation—that's margin-of-error territory. The FP4 curves closely track BF16 across all model sizes.

Zero-Shot Evaluation

On downstream tasks (Arc, BoolQ, HellaSwag, LogiQA, PiQA, SciQ, OpenbookQA, Lambada), FP4-trained models achieved competitive or occasionally superior performance compared to BF16.

That "occasionally superior" is wild. Sometimes the discretization acts as implicit regularization, preventing overfitting. We don't fully understand why, but we'll take it.

Fully Quantized LLaMA2 7B

In follow-up work, researchers trained LLaMA2 7B with weights, activations, AND gradients all in FP4. Initial training showed a small gap vs BF16. Then they added a short Quantization-Aware Fine-tuning (QAF) phase. The gap closed completely. Downstream tasks matched BF16.

This validates FP4's practical viability for end-to-end training. You can start in FP4, stay in FP4, and ship in FP4.

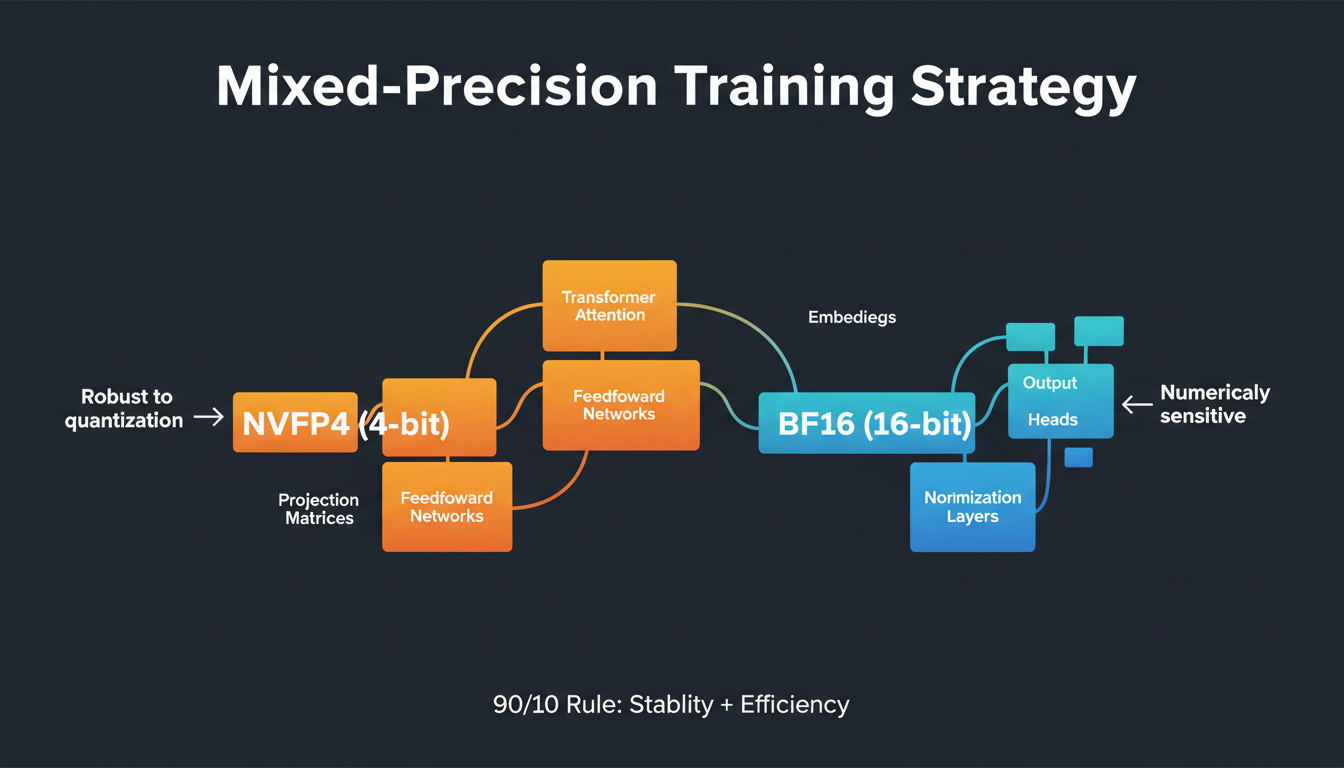

2. The Mixed-Precision Revelation

Here's the key insight that makes FP4 training work: not all layers are created equal.

Most layers—attention heads, feedforward networks, projection matrices—handle linear algebra. These are robust to quantization. But a few layers are numerically sensitive:

- Embeddings: Map discrete tokens to continuous vectors (boundary crossing)

- Output heads: Convert final representations to logits (precision matters)

- Normalization layers: Compute means/variances (accumulation errors)

The 90/10 Rule

90% of layers: NVFP4 (4-bit)

10% of layers: BF16 (16-bit)

Result: Stability + efficiency. The mixed-precision strategy is like having a Swiss Army knife—most jobs use the regular blade, but you keep the precision screwdriver for the tricky bits.

This hybrid approach maintains training stability while maximizing efficiency gains. You get most of the throughput improvement (since 90% of compute is in FP4) without sacrificing convergence reliability.

For Our SLM Ensemble

With 8 models using Mamba 3 + Transformer hybrid architecture plus MoE routers, we apply mixed precision selectively:

- Transformer attention: FP4

- Mamba 3 SSM layers: FP4

- MoE routers: BF16 (routing decisions need precision)

- Token embeddings: BF16

- Output heads: BF16

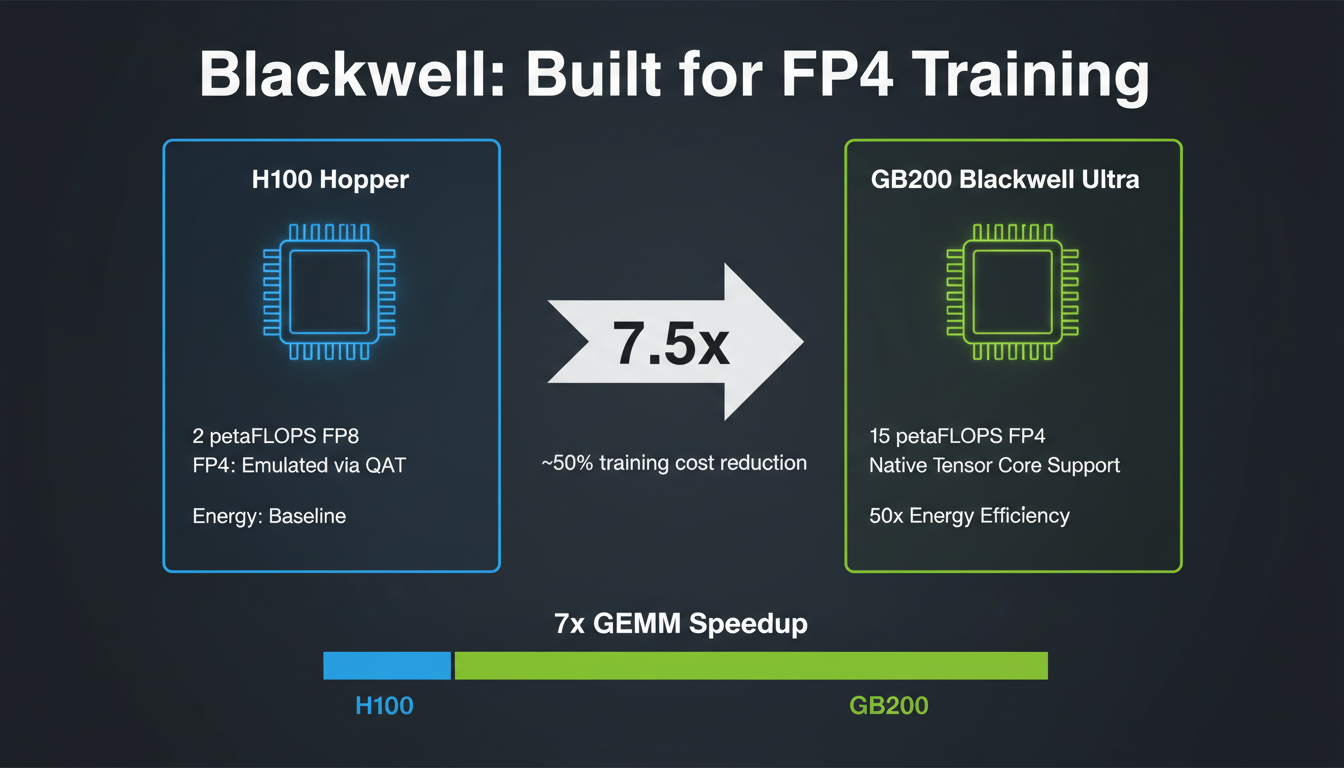

3. The Blackwell Advantage: 15 PetaFLOPS of FP4

Blackwell GPUs aren't just faster—they're designed for FP4 from the ground up.

H100 (Hopper, SM 90)

B200 (Blackwell, SM 100)

That's a 7.5x performance jump from Hopper to Blackwell Ultra for FP4 operations. The GEMM (matrix multiply) speedup is 7x. This isn't incremental—this is generational.

Training Cost Implications

For a 7B model trained on 150B tokens:

- BF16 on H100: ~500 GPU-hours

- FP4 on B200: ~250 GPU-hours (~50% reduction)

- Our 7-model ensemble: ~1,750 GPU-hours saved

At cloud rates (~$2/GPU-hour for Blackwell), that's $3,500 saved per training run. For iterative experimentation, those savings compound quickly.

SM Compatibility Warning

NVFP4 training support depends on compute capability:

- SM 100 (B100, B200): Full NVFP4 training support via Transformer Engine 2.7+

- SM 120 (RTX 5090): NOT supported yet—"MXFP8 not supported on 12.0+ architectures"

- SM 121 (GB10/DGX Spark): NOT supported yet—same TE limitation as SM 120

We use BF16 training on our local GB10 cluster for prototyping, then rent B200 time for production NVFP4 runs. JAX/Flax + TE has the same limitation. We're evaluating porting the CUTLASS kernels ourselves.

4. The Optimizer Challenge: Why Not AdamW?

Standard optimizers like Adam and AdamW maintain two state buffers per parameter: momentum and variance. These require numerical headroom to track tiny changes over billions of updates. At FP4 precision, that headroom doesn't exist.

Why We Use Muon Optimizer

We adopted Muon (matrix orthogonalization optimizer) for ultra-low-precision training. Key differences from AdamW:

- Quantized state buffers: Momentum/variance stored in FP8, not FP32

- Adaptive scaling: Per-layer scale adjustment based on gradient distribution

- Gradient clipping: More aggressive to prevent FP4 overflow

- Learning rate warmup: Longer warmup for stability at low precision

Research opportunity: Ultra-low-precision optimizers are an open frontier. Muon achieves ~2x computational efficiency vs AdamW and is used by Moonshot AI for scaled LLM training.

Could standard AdamW work with careful tuning? Maybe. But Muon gave us convergence reliability from day one, and in production, reliability beats theoretical purity.

5. QAT vs PTQ: When to Fine-Tune

You have two paths to NVFP4 models:

Post-Training Quantization (PTQ)

Fast, lightweight, no training data needed.

✓ Good for 7B+ models

✓ <1% accuracy loss typical

✓ 512 calibration samples sufficient

✗ Struggles with <7B models

✗ Limited accuracy recovery options

Quantization-Aware Training (QAT)

Fine-tune with quantization in forward pass.

✓ Better accuracy recovery

✓ Best for <7B models

✓ Matches or exceeds BF16 (e.g., Nemotron 4)

✗ Requires compute budget

✗ Needs training data

Decision Tree for Our SLMs

1. Start with PTQ for all 8 models (fast validation)

2. Check accuracy: If <1% loss → done. If 1-5% → consider QAT. If >5% → debug calibration data.

3. Apply QAT selectively to accuracy-critical models (e.g., C++ SLM, Debug SLM)

4. For 4B models, default to QAT from the start (PTQ gap too large)

NVIDIA Nemotron 4 achieved lossless FP4 quantization via QAT—matching or exceeding BF16 baseline performance. That's the gold standard. For critical production models, QAT is worth the compute investment.

6. The Four Over Six (4/6) Algorithm: Free Accuracy Gains

Here's a clever trick: E4M3 scales allow two nearby scale options for each block. The 4/6 algorithm quantizes each block twice (using both scale candidates), computes Mean Squared Error for both, and picks the one with lower error.

Why This Works

Near-maximal values in blocks suffer from large quantization jumps (e.g., trying to fit 5.9 into buckets at 4 and 6). By trying both scale factors, you sometimes find that a slightly different scale makes outliers land closer to available buckets.

Impact: Up to 19.9% gap reduction to BF16 baseline

Overhead: Essentially free (compute amortizes across training)

It's included in the latest TensorRT Model Optimizer releases. Enable it by default—there's no reason not to.

7. Implications for Our SLM Ensemble

Let's do the math for our 7-model architecture:

Training Cost Breakdown

Per model (average 6B params, 150B tokens):

BF16 on H100: ~400 GPU-hours

FP4 on Blackwell Ultra: ~200 GPU-hours (50% reduction)

7-model ensemble total:

BF16: 7 × 400 = 2,800 GPU-hours

FP4: 7 × 200 = 1,400 GPU-hours

Savings: 1,400 GPU-hours (~$2,800 at cloud rates)

Memory budget:

BF16: ~112 GB (needs multi-GPU setup)

FP4: ~32 GB (fits on single GB200 with 80GB spare)

But the real win isn't just cost—it's iteration speed. When training is 2x faster, we can experiment more. Try different architectures. Test hyperparameter variations. The faster feedback loop compounds into better models.

Our Training Strategy

- Train all 8 models in FP4 from scratch (not fine-tuning from BF16)

- Use mixed precision: 90% layers FP4, 10% BF16 (embeddings, routers, output heads)

- Muon optimizer with FP8 state buffers

- Enable 4/6 algorithm for free accuracy gains

- Apply QAT to C++ and Debug SLMs if PTQ shows >1% degradation

Rethinking Training Pipelines

FP4 training is production-ready. Not "in a few years"—now. NVIDIA's 12B model on 10 trillion tokens proved it scales. Our ensemble training validates it for specialized models. The Nemotron 4 results show it can be lossless with QAT.

But let's be honest about limitations: you need Blackwell for the full benefits. On Hopper, FP4 is emulated via QAT—you get memory savings but not the throughput boost. And there's still a small gap vs BF16 for very small models (<1B params) where quantization error dominates.

"What does it mean that intelligence compresses so well during training? We're not just saving memory—we're learning which gradient updates actually matter. There's something profound here about the nature of learning itself."

Will we see FP3? FP2? Probably not—the quantization error curve gets steep below 4 bits. But I said the same thing about FP4 two years ago, and here we are training trillion-token models at 4-bit precision. Never bet against the hardware folks.

Next up: How we built a hybrid Mamba 3 + Transformer architecture that everyone said was impossible to train. (Spoiler: FP4 mixed precision was key.)