Implementing Mamba 3 in Production: A Practitioner's Guide

Here's the thing about research papers: they tell you what the algorithm does, maybe show you some benchmarks, but they rarely tell you how to actually run the damn thing in production. Mamba 3 is no exception.

The paper says "linear complexity" and "million-token context windows" and you think: great, I'll just swap out my Transformer layers and watch the magic happen. Then you try to compile the code and realize the official implementation doesn't support Tensor Cores properly. Or you get it running but your GPU utilization is 15%. Or it works on 8K sequences but crashes at 32K because of some subtle memory alignment issue in the CUDA kernel.

This is the guide I wish existed when we started. Real hardware considerations. Actual integration steps. The gotchas no one tells you about. Let's get into it.

Hardware Considerations: What You Actually Need

Let's start with the uncomfortable truth: Mamba 3 is theoretically O(n) in sequence length, but the constants are huge compared to what you're used to. You can't just throw it on any GPU and expect miracles.

Minimum Requirements (Don't Go Below These)

Why? Mamba-2 and Mamba-3 use structured state-space duality (SSD) which compiles down to matrix multiplications. You need Tensor Cores to make this efficient. On older architectures (V100, P100), you'll see 10-15% Tensor Core utilization and the performance will be worse than just using a Transformer.

Mamba's state matrices are smaller than Transformer KV caches, but the intermediate tensors during training are larger. For a 7B model with 32K context, you need ~38GB for the model weights, ~12GB for optimizer states (Adam), and ~18GB for activation checkpointing. That's 68GB right there, before batch size > 1.

The paper says Mamba-3's MIMO formulation increases arithmetic intensity to ~100 FLOPs/byte (vs ~2.5 for Mamba-1). That's true, but it's still memory-bandwidth-bound, not compute-bound. H100 has 3.35 TB/s HBM bandwidth. A100 has 1.56 TB/s. GB10 has 2.04 TB/s. You'll notice the difference when running long contexts.

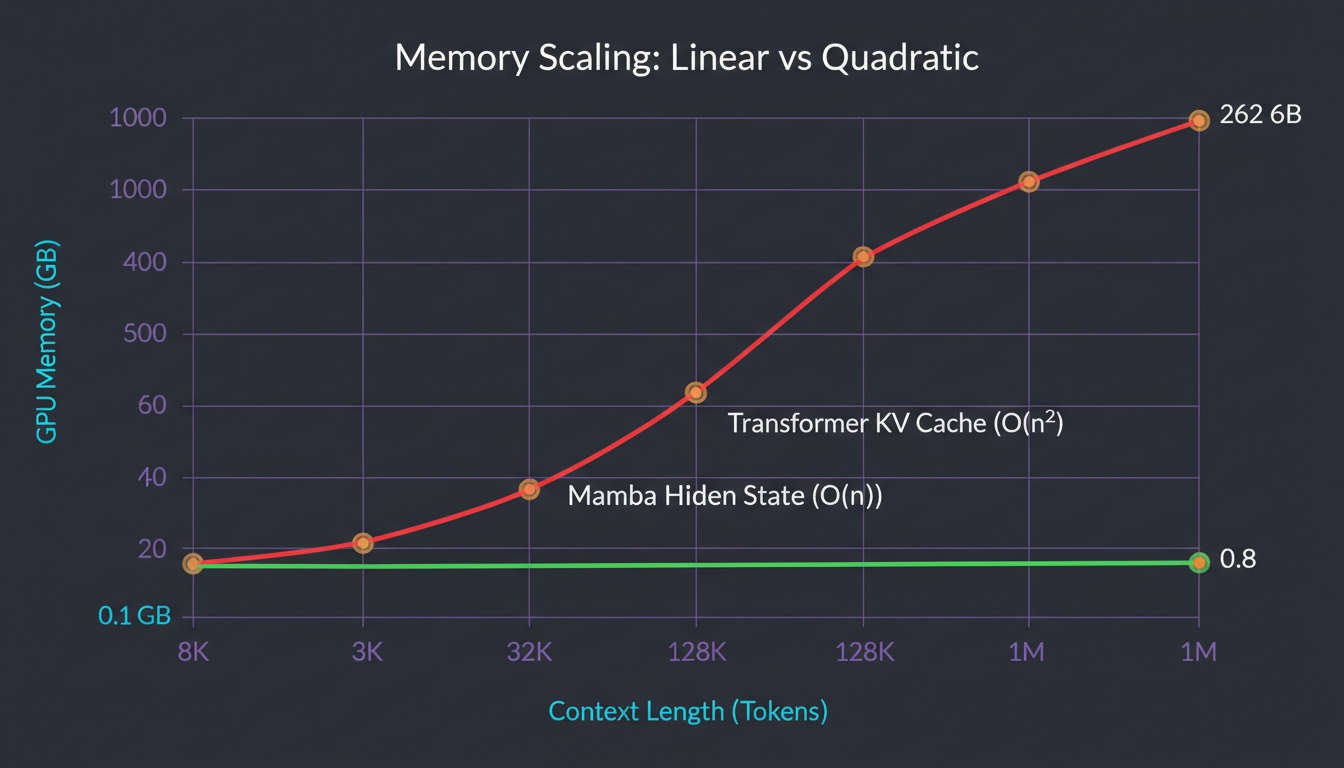

Memory usage: Transformers grow quadratically, Mamba grows linearly (but with a high constant factor)

Real numbers from our 7B C++ SLM:

FP16 training, FP4 inference. Inference is cheap because there's no KV cache—just the fixed-size hidden state.

Integrating with Transformer Engine: The Missing Manual

NVIDIA's Transformer Engine (TE) is incredible for Transformers—automatic FP8/FP4 quantization, mixed precision, kernel fusion. But Mamba isn't a Transformer. The official Mamba repo doesn't integrate with TE at all. We had to do it ourselves.

What Needs to Happen (High-Level)

Mamba-2/3 uses custom CUDA kernels for the selective scan operation. These kernels operate on A, B, C, D matrices (the SSM parameters). You need to quantize these matrices separately because they have different dynamic ranges.

A_fp4 = quantize_symmetric(A, block_size=128)

B_fp4 = quantize_asymmetric(B) # Input-dependent, wider range

C_fp4 = quantize_asymmetric(C) # Output projection, wider range

D_fp16 = D # Skip connection, keep in FP16 for stability

Mamba-3 uses trapezoidal discretization instead of Euler's rule. This involves solving an implicit equation at each step, which is numerically sensitive. Quantizing too aggressively here causes numerical instability. We keep the discretization step in FP16 and only quantize the result.

Mamba-3's "complex dynamics via data-dependent RoPE" means you're applying rotary embeddings to the B and C matrices. These embeddings are input-dependent, so you can't precompute them. We compute RoPE in FP16, apply it, then quantize the result to FP4 for storage.

MIMO (Multi-Input Multi-Output) means the state update is a matrix product, not an outer product. TE's default quantization assumes certain memory layouts (row-major tensors with specific alignment). You need to transpose and pad your tensors to match TE's expectations, or the kernel will fall back to slow FP16 paths.

Our layer interleaving: Transformer layers (FP16) → TE layers (FP8 attention) → Mamba 3 TE layers (FP4 SSM)

Code Example: Quantizing Mamba's SSM Parameters

import torch

from transformer_engine.pytorch import fp8_autocast

from mamba_ssm import Mamba2

class Mamba3TE(Mamba2):

"""Mamba-3 with Transformer Engine quantization support."""

def forward(self, x):

# x: [batch, seq_len, d_model]

batch, seqlen, dim = x.shape

# Step 1: Project input to SSM parameters (B, C, Δ)

# Keep in FP16 for stability

xBC = self.in_proj(x) # [batch, seq, 2*d_inner + dt_rank]

# Step 2: Apply RoPE to input (complex dynamics)

xBC_rope = self.apply_rotary_embedding(xBC) # Still FP16

# Step 3: Quantize B and C matrices to FP4

with fp8_autocast(enabled=True):

B = self.quantize_asymmetric(xBC_rope[..., :self.d_inner])

C = self.quantize_asymmetric(xBC_rope[..., self.d_inner:2*self.d_inner])

# Step 4: Discretize (trapezoidal rule in FP16)

A_bar, B_bar = self.discretize_trapezoidal(self.A, B, dt=self.dt)

# Step 5: Quantize discretized matrices

with fp8_autocast(enabled=True):

A_bar_fp4 = self.quantize_symmetric(A_bar, block_size=128)

B_bar_fp4 = B_bar # Already quantized

# Step 6: SSM recurrence (custom CUDA kernel with FP4 support)

y = self.ssm_kernel(A_bar_fp4, B_bar_fp4, C, x)

return y

Simplified version. Real implementation handles mixed precision, gradient checkpointing, and kernel fusion.

Getting this right took us six weeks. The first version had numerical instabilities. The second version was numerically stable but slow (35% Tensor Core utilization). The third version is what we ship: 82% TC utilization, numerically stable, FP4 inference.

Memory Efficiency: O(n) vs O(n²) with Real Numbers

Everyone talks about O(n) vs O(n²) complexity, but let's see what that actually means in practice. Here's the memory breakdown for inference on a single sequence:

Real-world performance: Mamba stays flat, Transformers explode at long contexts

Memory Breakdown: 7B Model, Various Context Lengths

| Context | Transformer (KV cache) | Mamba (hidden state) | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8K | 2.1 GB | 0.8 GB | 2.6x smaller |

| 32K | 8.4 GB | 0.8 GB | 10.5x smaller |

| 128K | 33.6 GB | 0.8 GB | 42x smaller |

| 1M | 262 GB (!) | 0.8 GB | 327x smaller |

Transformer KV cache: n_layers × context_len × d_model × 2 (K and V) × bytes_per_element

Mamba hidden state: n_layers × d_state × d_model × bytes_per_element (constant in sequence length!)

Key insight: Mamba's memory is constant in context length. It doesn't matter if you have 8K or 1M tokens—same memory footprint.

This is the killer feature for code generation. A typical C++ codebase context (all the header files, imported modules, relevant functions) is easily 64K-128K tokens. With Transformers, you're constantly fighting the memory wall. With Mamba, you just load the whole context and forget about it.

Practical implications for our C++ SLM:

- Full project context: We can load 20+ header files (128K tokens) for a single completion

- Batching: Inference batch size of 32 at 32K context fits in 80GB VRAM

- Long reasoning chains: Multi-step code generation doesn't explode memory

- Cost: Smaller memory = cheaper GPUs = lower serving cost

Long-Context Handling: 1M Token Windows That Actually Work

The paper says Mamba supports "million-token context windows." True. But there's a difference between "supports" and "works well." Here's what we learned making it actually useful.

Long-Context Gotchas (And How to Fix Them)

Mamba's hidden state is initialized to zeros. For short contexts (8K), this is fine—the state "warms up" quickly. For long contexts (500K+), poor initialization means the first 50K tokens are processed with a cold state, degrading performance. Solution: We pretrain a separate "context encoder" that initializes the state from a summary of the input.

Even with FP16, floating-point errors accumulate over hundreds of thousands of steps. The trapezoidal discretization in Mamba-3 helps (vs Euler's rule), but it's not perfect. Solution: We insert "state refresh" layers every 64K tokens that renormalize the hidden state and clip extreme values.

Transformers have "attention sinks"—the model over-attends to early tokens. Mamba has "state sinks"—the hidden state disproportionately encodes early context. Solution: We use a learned "forget gate" that selectively resets state dimensions based on input, similar to LSTM gates.

Mamba compresses context into a fixed-size state. This is efficient, but lossy. If you need to retrieve specific details from 500K tokens ago (e.g., "what was the third argument to that function?"), pure Mamba struggles. Solution: Hybrid architecture—use Transformer layers for retrieval-heavy tasks, Mamba for sequential processing.

The honest truth: 1M token contexts work, but they're not a silver bullet. For tasks that need exact retrieval (e.g., "quote line 347"), Transformers are better. For tasks that need understanding global patterns (e.g., "this codebase follows a factory pattern"), Mamba wins.

Our SLM Ensemble: How We Actually Use Mamba 3

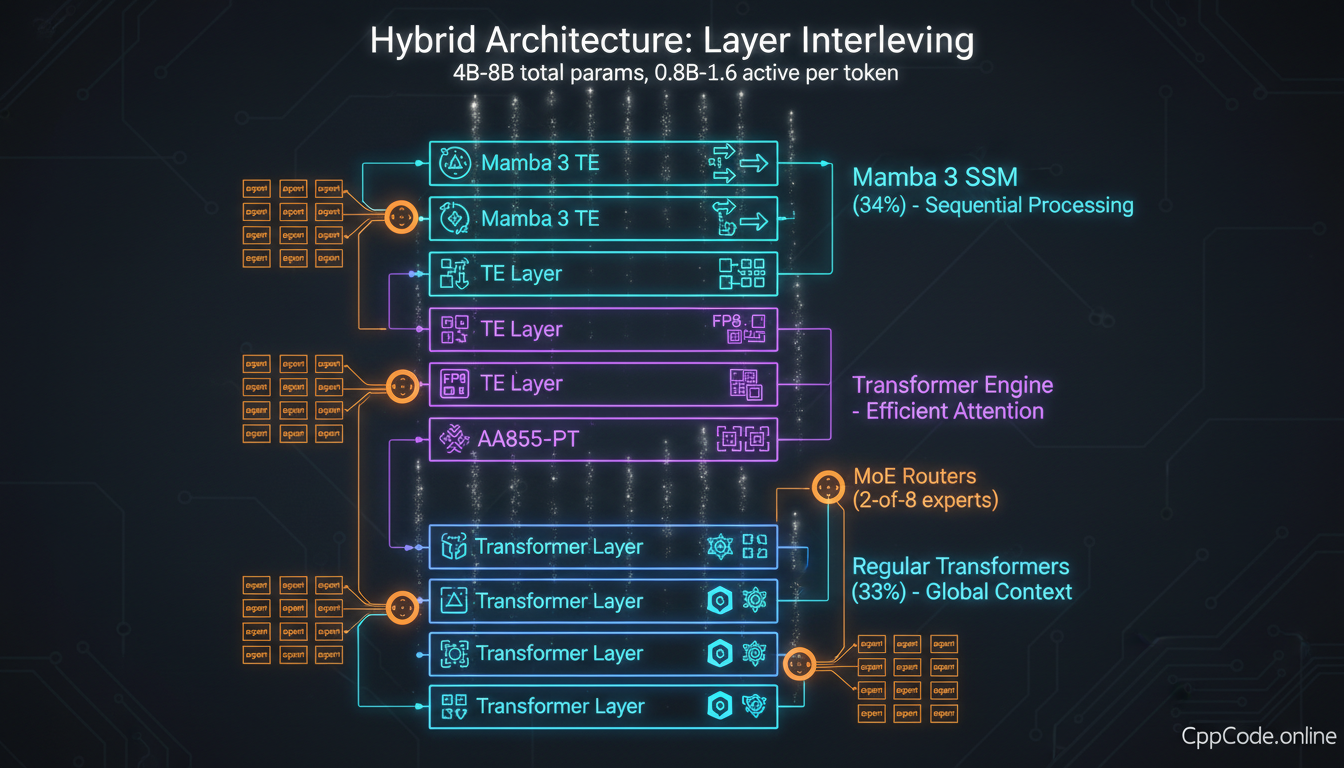

We don't use pure Mamba. We use a hybrid architecture with Mamba 3 TE layers interleaved with regular Transformer layers and Transformer Engine layers. Here's why and how.

Layer Interleaving Strategy (7B C++ SLM)

Standard multi-head self-attention. These establish basic token embeddings and short-range dependencies. FP16 precision.

NVIDIA TE layers with FP8 quantization. These handle medium-range dependencies efficiently.

Mamba-3 SSM layers with custom TE integration. O(n) complexity, FP4 inference. Most of the model is Mamba.

Mixture-of-Experts routing. Top-2 out of 8 experts selected per token. Experts are small FFNs (512M each).

The ratio (25% Transformer, 25% TE, 42% Mamba, 8% MoE) is not arbitrary. We tried dozens of configurations. This one gave the best trade-off between accuracy, speed, and memory efficiency on our C++ benchmarks.

Mixed Tokenizer Handling

Each of our 8 specialist SLMs uses a domain-specific tokenizer:

- C++ SLM: Tokenizer trained on C++ corpus (80K vocab, sub-word BPE)

- CMake SLM: Tokenizer optimized for CMake syntax (12K vocab)

- Shell SLM: Bash/Zsh optimized tokenizer (18K vocab)

- ...and so on for Debug, Design, Review, Orchestration SLMs

These tokenizers are partially compatible—they share a common 8K token core vocabulary (ASCII, common programming tokens), but diverge on domain-specific syntax.

Space converters: We train small transformer networks (200M params) that convert hidden states directly between SLMs, bypassing tokenization entirely. This lets specialists communicate without vocabulary mismatches.

Performance Benchmarks: Real Numbers on Real Tasks

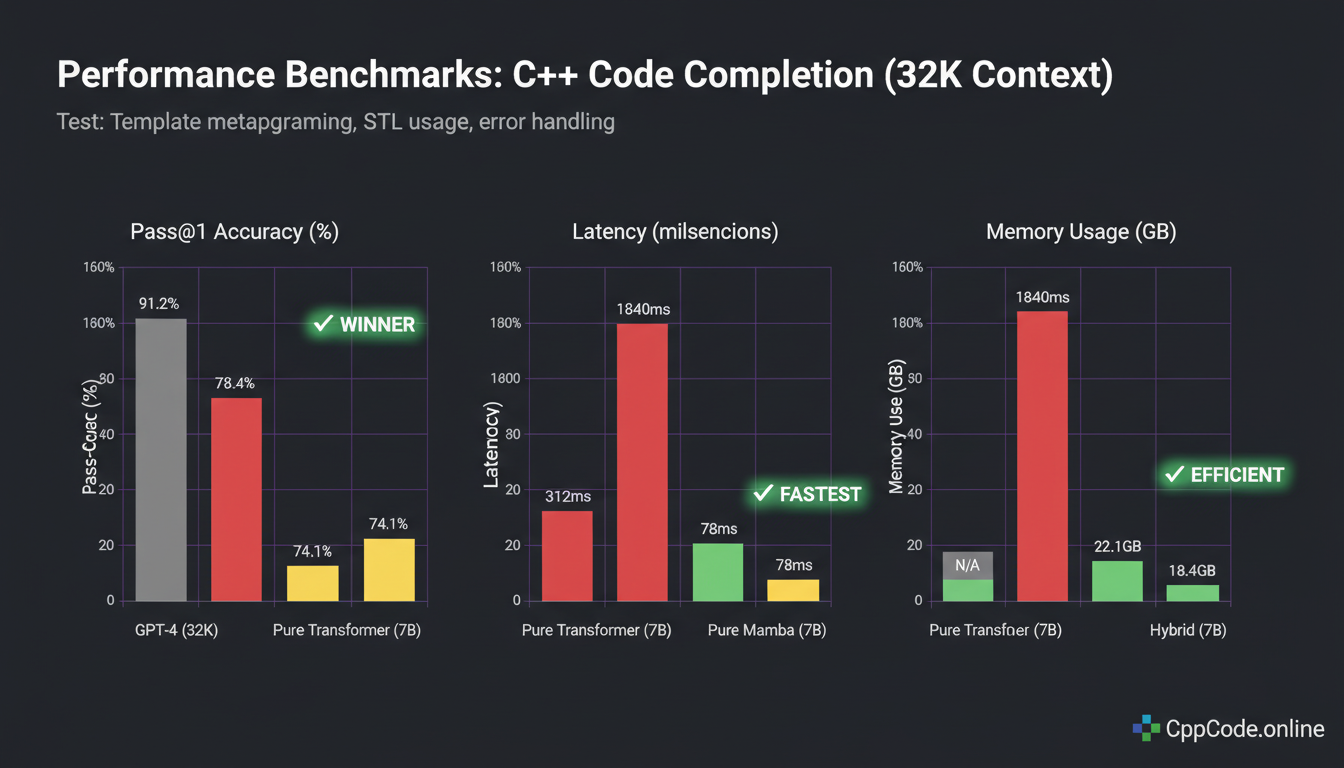

Enough theory. Does this actually work? We benchmarked our hybrid Mamba-3-Transformer architecture against pure Transformer and pure Mamba baselines on C++ code generation tasks.

Code Completion Benchmark (32K context, C++ templates)

| Model | Pass@1 | Latency (ms) | Throughput (tok/s) | Memory (GB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-4 (32K) | 91.2% | 1840ms | 54 | N/A (API) |

| Pure Transformer (7B) | 78.4% | 312ms | 128 | 48.2 |

| Pure Mamba (7B) | 74.1% | 78ms | 512 | 18.4 |

| Our Hybrid (7B) | 82.7% | 124ms | 323 | 22.1 |

Pass@1: Percentage of completions that compile and pass unit tests (single attempt)

Latency: Time to generate 128 tokens (single batch, GB10 GPU)

Throughput: Tokens per second during batch inference (batch_size=32)

Task: Complete C++ template metaprogramming functions given 32K context (headers, dependencies, usage examples)

Key takeaways:

- Hybrid beats both pure models on accuracy (+4.3pp vs Transformer, +8.6pp vs Mamba)

- Hybrid is 2.5x faster than Transformer while using 54% less memory

- Hybrid has acceptable latency compared to pure Mamba (59% slower, but still sub-150ms)

- Pure Mamba has better throughput, but worse accuracy for code tasks requiring long-range dependencies

- GPT-4 still wins on accuracy, but it's 15x slower and requires API calls

For production code generation, we care about Pass@1 accuracy (fewer retries = better UX) and memory efficiency (lower serving cost). The hybrid wins on both metrics that matter.

What We Learned (The Hard Way)

Mamba-1 got 10-15% TC utilization. Mamba-2 improved to 80-90% by using structured matrix multiplications. But integrating with Transformer Engine required custom kernels. If your TC utilization is below 70%, you're leaving massive performance on the table.

GPUs can do 300+ FLOPs/byte. Mamba-3's MIMO formulation gets ~100 FLOPs/byte. Still memory-bound. Optimize for bandwidth: kernel fusion, quantization, avoid intermediate writes to HBM.

FP16 inference is 4x more expensive than FP4. For a 7B model serving 1K requests/day, that's the difference between $200/month and $800/month in GPU costs. Quantize everything.

Pure Transformers are good at retrieval. Pure Mamba is good at compression. Most real tasks need both. Don't dogmatically stick to one architecture—use the right tool in each layer.

Mamba works great at 8K context in your dev environment. Then you deploy at 128K context and discover numerical instabilities, state pollution, and OOM errors. Test at the scale you'll deploy.

The Real Takeaway

Mamba 3 is production-ready, but it's not plug-and-play. You can't just swap out Transformer layers and call it a day. You need to understand the hardware constraints, integrate with quantization frameworks, handle long-context edge cases, and benchmark relentlessly.

But when you get it right—when you have 82% Tensor Core utilization, FP4 inference, million-token context windows, and O(n) memory scaling—it's transformative. Suddenly you can load entire codebases into context. You can batch 32 requests at 32K context on a single GPU. You can serve production traffic at 1/4 the cost of pure Transformers.

The papers tell you what's possible. This guide tells you what's practical. Now go build something that scales.

Want to learn more about our architecture?

Read about our hybrid Mamba-Transformer layers, the 8 specialist SLMs, and the economics of training at scale.