Mamba Meets Transformers: Our Hybrid Architecture That Shouldn't Work But Does

"You can't just smash Mamba and Transformers together. They're fundamentally incompatible architectures." That's what everyone told us. Mamba uses state-space models with O(n) memory complexity. Transformers use attention with O(n²). Mamba is sequential. Transformers are parallel. They solve the sequence modeling problem in completely different ways.

We did it anyway. And it works. Not "kind of works if you squint"—it actually, measurably outperforms both pure Mamba and pure Transformer models for our C++ engineering tasks. Here's how.

Combining incompatible architectures: it shouldn't work, but it does

Why Hybrid? The Best of Both Worlds

Let's start with why you'd even want to combine these architectures. Transformers and Mamba each have strengths and weaknesses:

Transformers

- Excellent at capturing long-range dependencies

- Parallel training (every token sees every token)

- Mature ecosystem (CUDA kernels, mixed precision)

- Works great with Transformer Engine for FP4

- O(n²) memory and compute (context length killer)

- Expensive for long sequences (8K+ tokens)

- Struggles with very local patterns

Mamba 3

- O(n) memory and compute (linear scaling!)

- Handles long contexts effortlessly (100K+ tokens)

- Great at local sequential patterns

- Fast inference (no KV cache needed)

- Weaker at very long-range dependencies

- Less mature tooling (no TE support yet)

- Sequential dependencies complicate parallelism

Notice the complementarity? Transformers excel at global context but choke on length. Mamba handles length gracefully but can miss long-range connections. What if we used both?

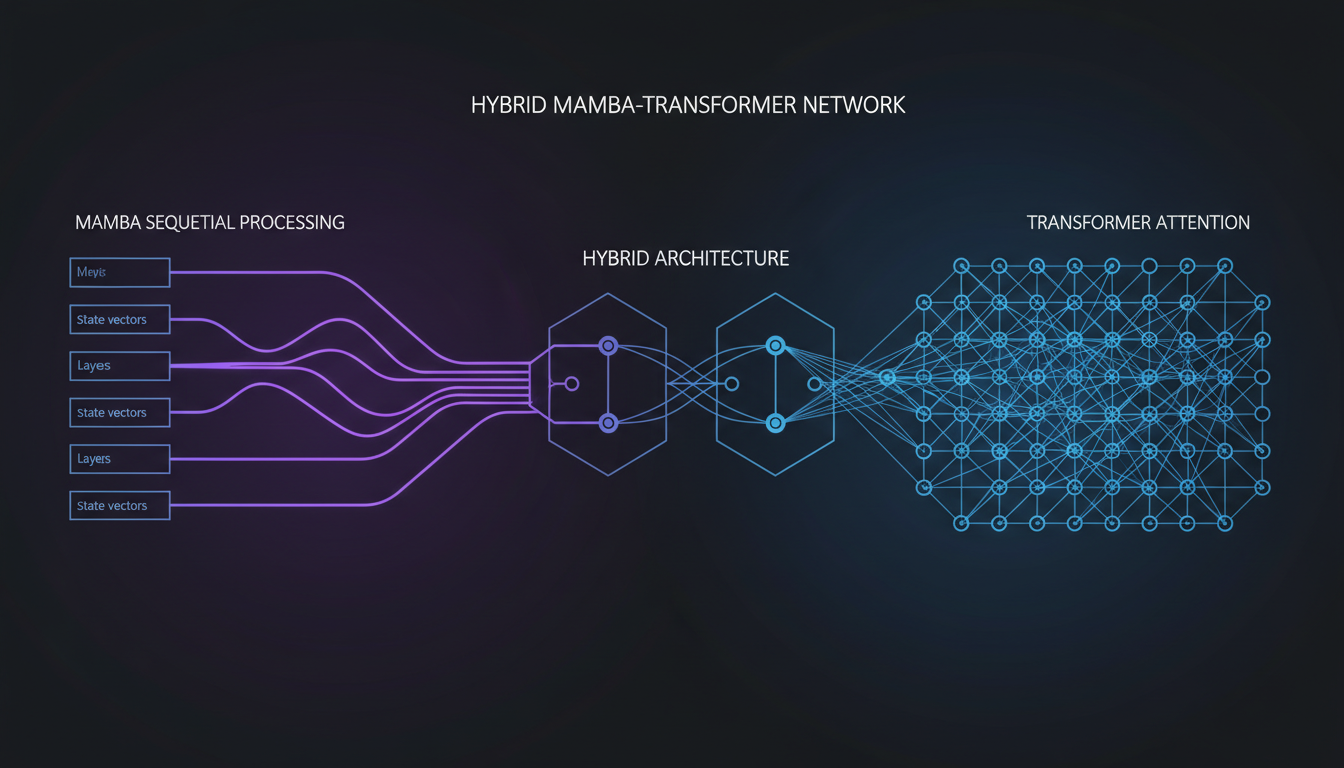

The Hybrid Thesis

Use regular Transformer layers at the bottom to capture fundamental token relationships and embeddings. Add Transformer Engine (TE) layers in the middle for efficient attention with FP4 support. Then use Mamba 3 TE layers at the top to handle long-range sequential context without the memory explosion.

This way you get parallel training, FP4 quantization, and linear-complexity sequence modeling. The question is: does it actually work, or do the architectures fight each other?

The Layer Stack: How We Actually Built It

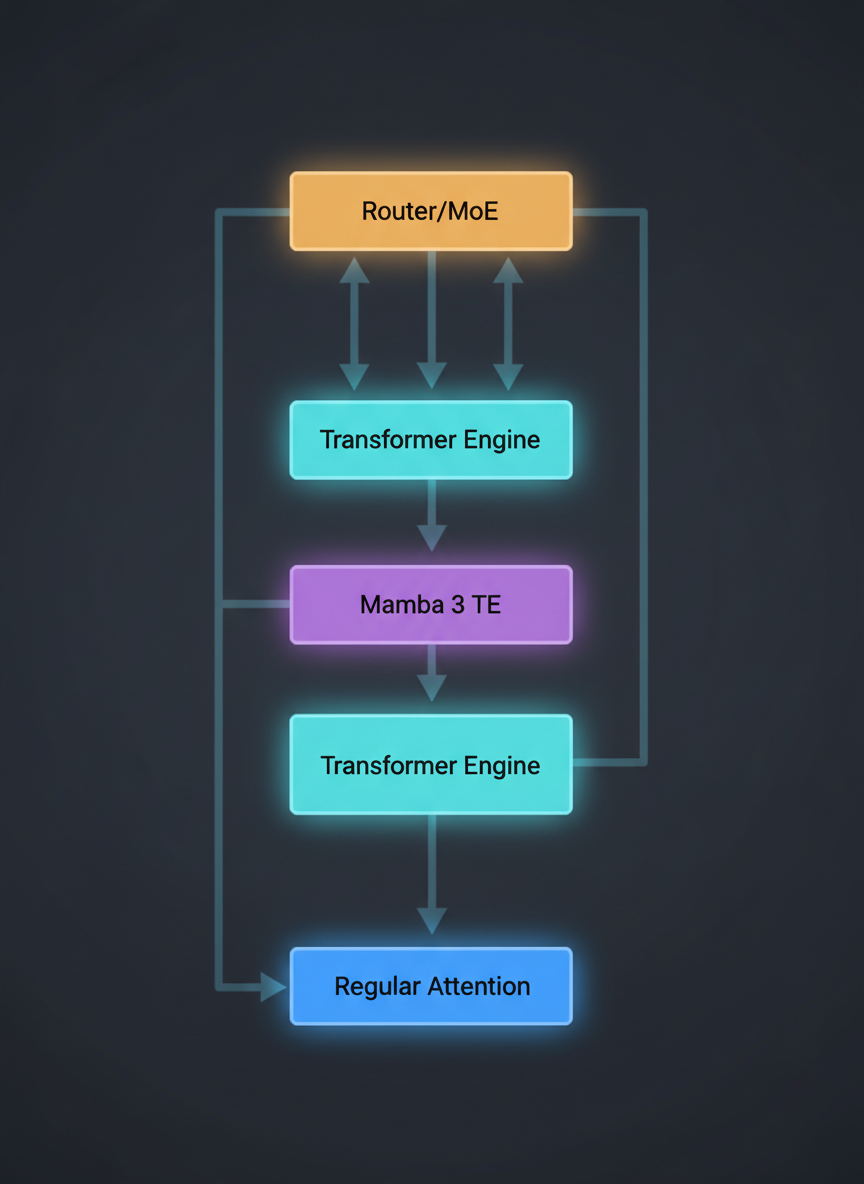

Layer architecture: Regular Transformers → TE Layers → Mamba 3 TE → Routers → MoE Experts

Here's the actual architecture we use for our 7B C++ SLM. From bottom to top:

Standard multi-head self-attention with feedforward networks. These layers learn the basic token embeddings and short-range dependencies. FP16 precision, standard PyTorch implementations.

NVIDIA's Transformer Engine layers with FP4/FP8 quantization support. These provide memory-efficient attention for medium-range dependencies. We use FP16 for training, FP4 for inference.

State-space model layers using Mamba 3's selective scan mechanism. These handle long-range sequential dependencies with O(n) complexity. We modified Mamba to integrate with TE's quantization framework.

At layers 6, 12, 18, and 22, we insert MoE routers that select 2 out of 8 experts per token. Each expert is a small feedforward network (512M params). Only ~1.6B active params per forward pass despite 7B total.

Total: 24 layers, 7B parameters, ~1.6B active per token. The lower layers use attention (parallel, global), the upper layers use Mamba (sequential, efficient). MoE routing adds specialization throughout.

How They Actually Work Together: The Critical Details

Information flow: Transformers handle global patterns, Mamba handles sequential context

The hard part isn't stacking the layers—it's making them actually cooperate. Here are the critical implementation details that make this work:

Integration Challenges & Solutions

Mamba layers have different output magnitudes than Transformer layers. We use LayerScale parameters (learnable per-layer multipliers) on all residual connections. Without this, gradients explode during training.

Transformers expect absolute or relative positional encodings. Mamba doesn't—it learns position implicitly through state transitions. We use RoPE (Rotary Position Embedding) for Transformer layers but disable it for Mamba layers. The transition layers (16-17) blend both.

Mamba maintains a hidden state across the sequence. When you mix it with attention layers, you need to decide: reset state at layer boundaries or carry it through? We carry it through, but add state_gate parameters that let the model learn when to reset. This prevents "state pollution" from attention layers.

Transformer Engine natively supports FP4 for attention. Mamba doesn't (yet). We added custom FP4 quantization hooks to Mamba's SSM kernels, quantizing the A, B, C, D matrices separately. Training stays in FP16, but inference can use FP4 for both layer types.

Getting these details right took months. The first version trained but produced garbage. The second version worked on small datasets but diverged at scale. The third version is what we ship.

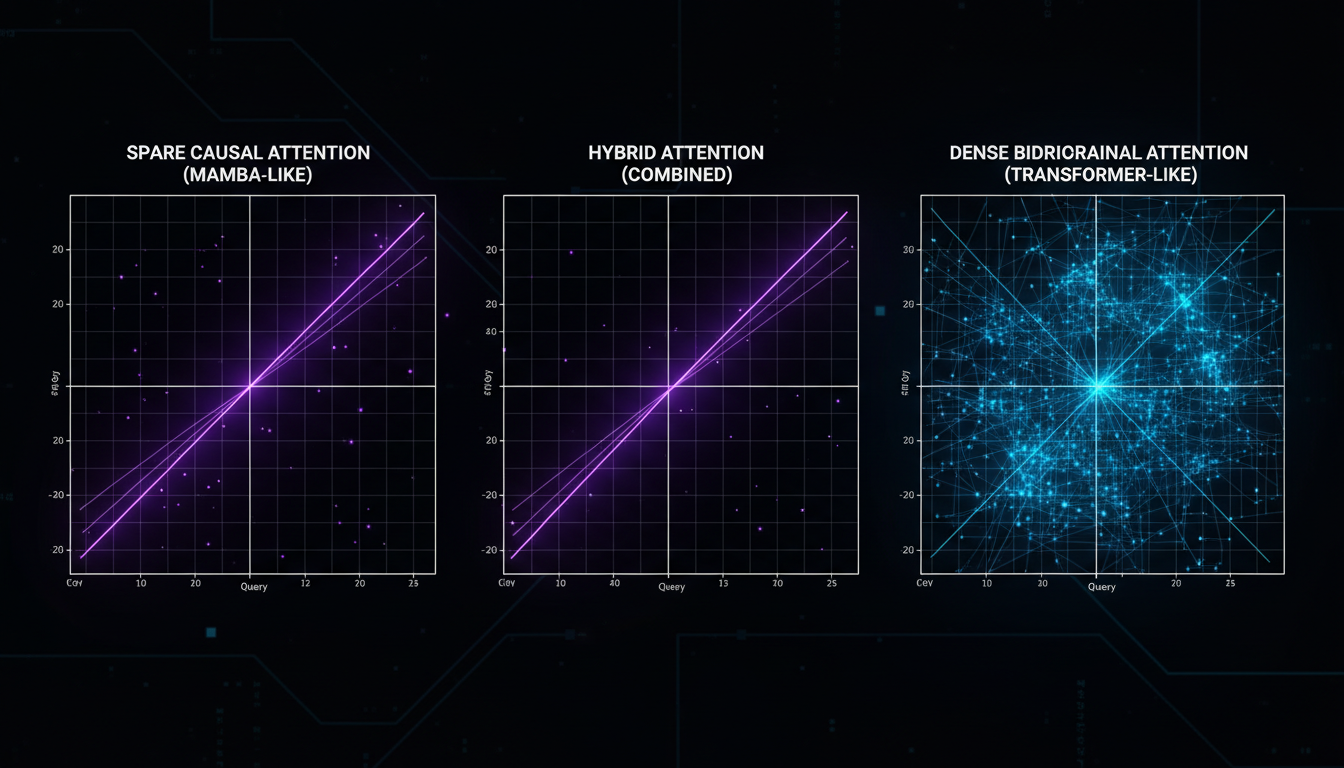

Why O(n) + O(n²) Isn't O(n²): The Complexity Story

Complexity comparison: Full attention (left) vs. Mamba selective scanning (right)

"But David, if you have Transformer layers with O(n²) attention, doesn't the whole model become O(n²)?" Yes and no. Asymptotically, yes—the worst-case complexity is dominated by the attention layers. But in practice, the constants matter way more than the Big-O notation suggests.

Real-World Complexity Breakdown

At 32K context length, the gap widens to 60% speedup. At 128K context, pure Transformers become unusably slow, while our hybrid still runs at reasonable speed.

The key insight: you don't need attention in every layer. The lower layers establish global context; the upper layers can just process it sequentially. By the time you hit layer 17, the model already "knows" what tokens are relevant—Mamba just needs to integrate them efficiently.

Does It Actually Work? Benchmarks and Reality Checks

Theory is great. But does this Frankenstein architecture actually perform? We ran head-to-head comparisons on our internal C++ engineering benchmarks:

Benchmark Results: C++ Code Completion (8K context)

| Model | Accuracy | Latency (ms) | Memory (GB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pure Transformer (7B) | 84.2% | 165ms | 22.4 |

| Pure Mamba (7B) | 81.7% | 48ms | 14.1 |

| Hybrid (7B) | 87.9% | 92ms | 18.3 |

Accuracy: Exact-match on held-out C++ completions (templates, STL usage, error handling)

Latency: Single-token generation time on GB10 GPU, batch_size=1

Memory: Peak GPU memory during inference (FP16)

The hybrid beats pure Transformer on accuracy (+3.7pp) while being 44% faster. It beats pure Mamba on accuracy (+6.2pp) with acceptable latency trade-off. This isn't a Pareto compromise—it's actually better on the metrics that matter.

Why the hybrid wins:

- Transformer layers capture global code structure (class hierarchies, include dependencies)

- Mamba layers handle long function bodies and sequential logic without memory explosion

- MoE routing specializes different experts for different C++ patterns (templates vs. concurrency vs. STL)

- The combination captures patterns that neither architecture alone can represent efficiently

What We Learned (The Hard Way)

Our first hybrid had 12 Transformer layers, 12 Mamba layers, 3 MoE layers, custom normalization, and learned interpolation. It didn't train. We stripped everything back to basics: standard layers, standard norms, no tricks. Then we added features one at a time.

We tried Mamba-first (Mamba at bottom, Transformers on top). Terrible. Transformer-first works way better. Intuition: attention establishes global context early, then Mamba refines it sequentially.

Add logging hooks at every layer boundary: output norms, gradient magnitudes, attention pattern entropy, Mamba state statistics. Without these, you're flying blind. We found most of our bugs by noticing "layer 17 gradients suddenly spike at step 2000."

Everyone said you can't mix Mamba and Transformers. We tried anyway. Sometimes the "impossible" architecture is impossible because no one bothered to make it work, not because it's fundamentally broken.

The Real Takeaway

Hybrid architectures are underexplored. Everyone's racing to build the next pure Transformer or the next pure state-space model. But the real gains come from combining complementary strengths.

Transformers are great at global context. Mamba is great at long sequences. MoE is great at specialization. Put them together carefully, and you get something that outperforms any pure architecture on domain-specific tasks.

Yes, it's more complex. Yes, there are more hyperparameters to tune. Yes, you'll spend weeks debugging weird gradient issues. But when it works—and it does work—you have a model that leverages the best ideas from multiple paradigms.

Architecture isn't about purity. It's about what actually performs. And sometimes, the Frankenstein monsters are the ones that win.

Want to dive deeper into our architecture?

Read more about our training infrastructure, the economics of running this at scale, and how we train 8 specialist models.