The Honest Truth About Training AI on GB10: Our Grace Blackwell Journey

When NVIDIA announced Project DIGITS at CES 2025—now shipping as DGX Spark—we knew this was the hardware we'd been waiting for. A Grace Blackwell superchip with 128GB of unified LPDDR5X memory, sitting on your desk, capable of running and fine-tuning models up to 200 billion parameters. Here's what we actually learned deploying a cluster of these things.

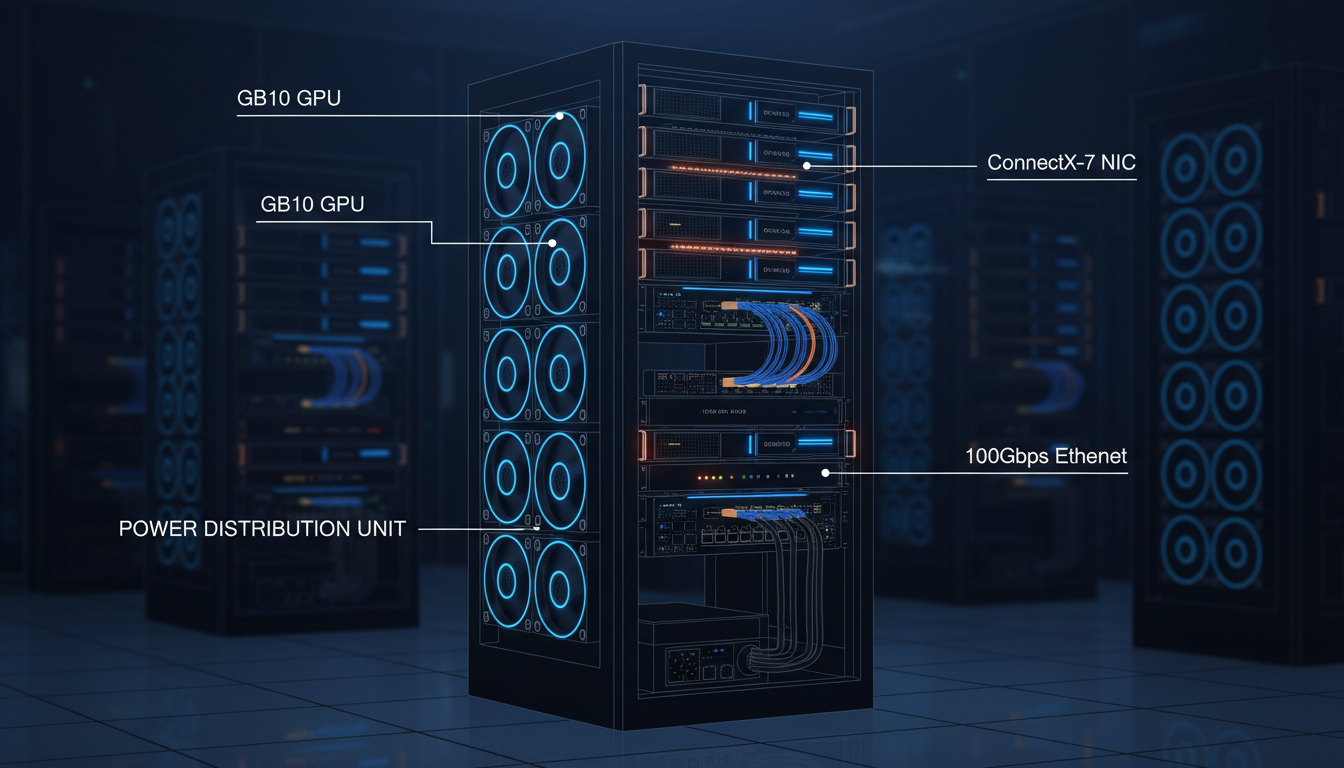

Our DGX Spark cluster: compact form factor, serious AI capability

What the GB10 Actually Is

The GB10 is NVIDIA's Grace Blackwell Superchip—a single package containing both a Grace ARM CPU and a Blackwell GPU, connected via NVLink-C2C at 600 GB/s. It's not a discrete GPU you slot into a motherboard. It's a complete system-on-chip designed from the ground up for AI workloads.

GB10 Superchip: The Real Numbers

The key insight: 128GB of unified memory means no PCIe bottleneck. The CPU and GPU share the same memory pool with cache-coherent access. This is why you can run 200B parameter models on what looks like a Mac Mini.

The DGX Spark ships at $3,999 with 4TB NVMe storage. Partners like ASUS offer the Ascent GX10 at $3,000. For context, that's roughly the price of an RTX 5090 gaming rig, but with 128GB of AI-accessible memory instead of 32GB.

Why 128GB Unified Memory Changes Everything

Traditional GPU training has a fundamental problem: your model weights live in GPU VRAM, your training data lives in system RAM, and everything has to cross the PCIe bus. Even PCIe 5.0 x16 tops out at ~64 GB/s. The GB10's unified memory architecture eliminates this bottleneck entirely.

What You Can Actually Run

For our 8-model SLM ensemble (4B-8B params each), a single GB10 can hold the entire ensemble in memory for inference. During training, we can work on one model at a time with plenty of room for optimizer states, activations, and data batches.

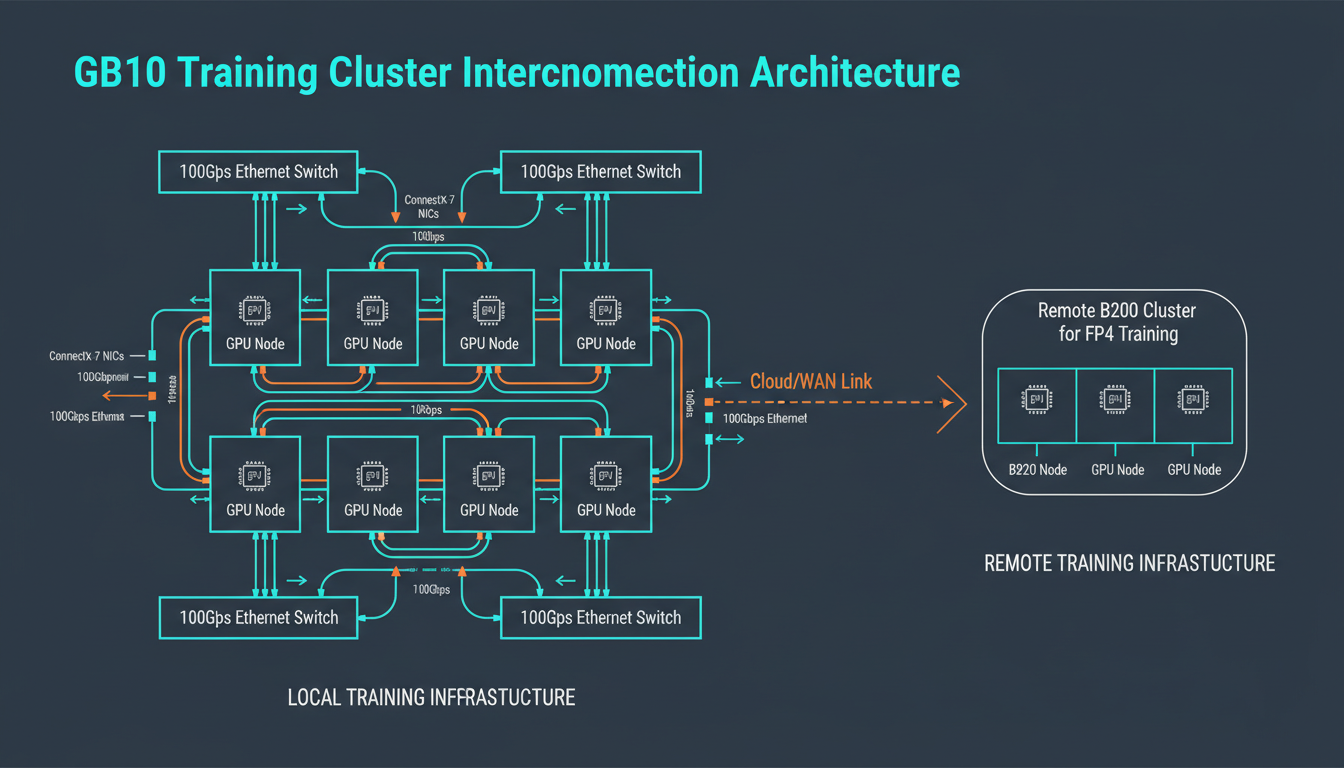

Connecting Multiple GB10s: ConnectX-7 Reality

DGX Spark networking: 10GbE LAN + ConnectX-7 for system linking

Each DGX Spark includes a ConnectX-7 NIC for linking systems together. NVIDIA advertises 200 Gbps, but there's a catch worth knowing about.

Networking Reality Check

PCIe x4 Limitation: The GB10 SoC can only provide PCIe Gen5 x4 per device (~100 Gbps). NVIDIA uses ConnectX-7's multi-host mode to aggregate two x4 links for the advertised 200 Gbps—but in practice, each link saturates at ~96 Gbps.

Ethernet Only (No VPI): The internal ConnectX-7 is Ethernet-only, not VPI (Virtual Protocol Interconnect). No native InfiniBand option—you get RoCE (RDMA over Converged Ethernet) instead. Fine for our use case, but worth knowing.

Switch Recommendation: A 100 Gbps switch is practical. 200 Gbps switches are overkill unless you're running 60+ parallel streams with jumbo frames to actually hit ~180 Gbps. We use 100GbE and it's plenty.

What We Actually Use

10GbE LAN: Standard networking for data loading, model checkpointing, and general connectivity. Sufficient for data parallel training where gradient syncs happen every few hundred milliseconds.

ConnectX-7 (100 Gbps practical): High-speed RoCE link for connecting DGX Spark units. We treat it as 100G, not 200G—less configuration headache.

WiFi 7 + Bluetooth 5.3: Desktop convenience. Surprisingly useful for quick prototyping without running cables.

We run 20+ DGX Spark units in our lab interconnected via our SN3700 switch fabric. For data parallel BF16 training, this gives us serious throughput. The PCIe x4 limitation only matters if you're doing microsecond-scale tensor parallelism—which we're not on desktop hardware anyway.

Our Training Pipeline

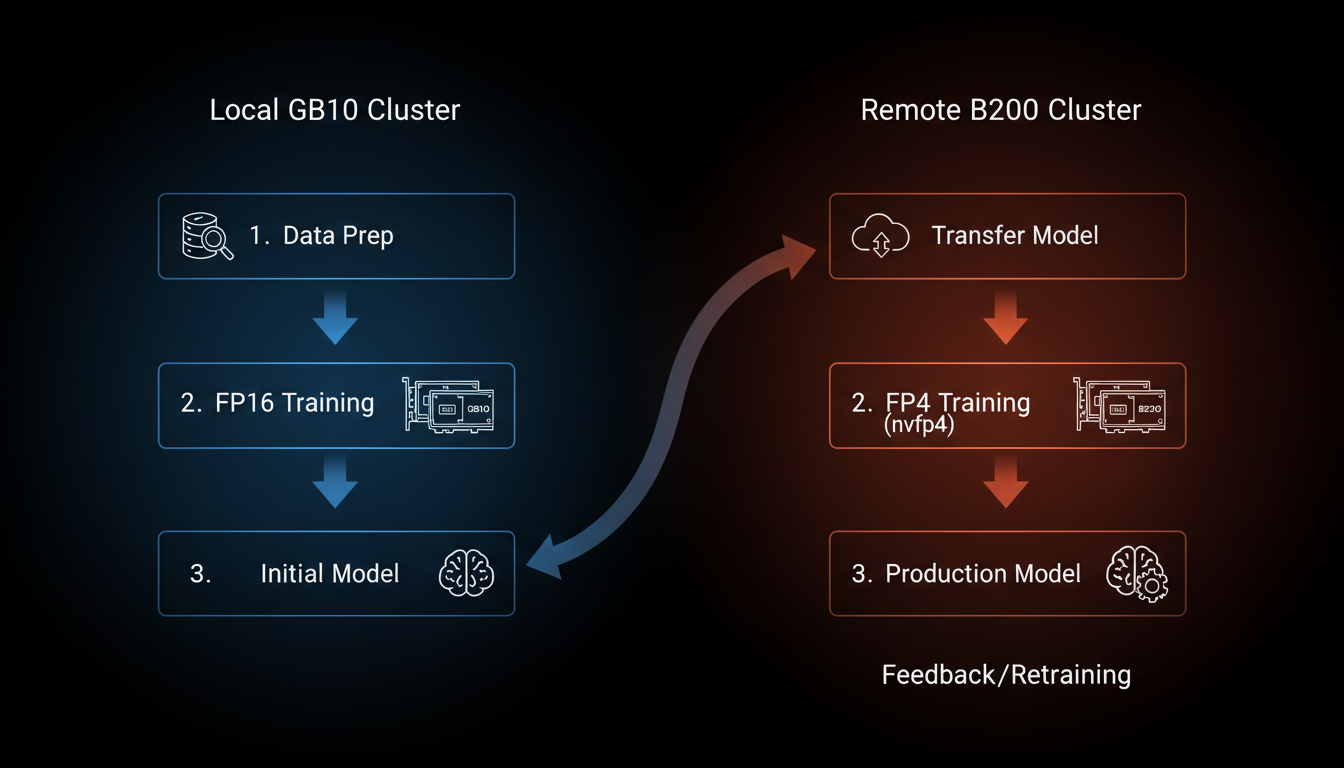

Our workflow: local experimentation on DGX Spark, scale-out to cloud B200 for final runs

The Workflow

Data curation, architecture experiments, hyperparameter sweeps, ablation studies. All in BF16 precision—NVFP4/MXFP8 training isn't supported on SM 121 yet. 128GB unified memory means realistic batch sizes, not toy examples.

When a model looks promising, we validate across all 4 units with data parallel BF16 training. This catches distributed training bugs before we spend cloud money.

For the final production runs with 100B+ tokens, we rent B200 time (SM 100). B200 supports NVFP4 training via Transformer Engine—2x throughput vs BF16. The HBM3e bandwidth (8 TB/s) makes the cloud cost worthwhile for long runs.

NVFP4 inference does work on GB10. We deploy our quantized models back to local hardware for serving. 1 PFLOP of FP4 performance is plenty for inference.

Curriculum Learning: The Nemotron Nano 3 Way

Here's something they don't tell you in the papers: you can't just throw 1M context at a model from day one and expect it to learn anything useful. The model will happily overfit to the structure of very long documents while completely forgetting how to handle the short, punchy queries that make up 90% of real-world use. NVIDIA figured this out with Nemotron Nano 3, and we stole their playbook shamelessly.

The insight is simple: train on short context first, extend later. It's like teaching someone to read—you don't start with War and Peace. You start with "The cat sat on the mat" and work your way up. Except here, "the mat" is 4K tokens and "War and Peace" is a 1M token codebase with 47 interdependent header files.

The Four Phases of Training

The bulk of learning happens here. Short context, high throughput, pure language modeling. Your model learns syntax, semantics, facts, and the basic patterns of code. This is where you burn 94% of your training tokens.

Same short context, but now you're feeding it the good stuff—curated, high-quality examples. Think of it as teaching the model to write like a senior engineer, not a StackOverflow copy-paster. Still cheap to run, huge quality impact.

Here's where things get interesting—and expensive. You're teaching the model to actually use that extended context window. Mix of document lengths, heavy on the long stuff. This is where you need real networking bandwidth and ZeRO-3/FSDP.

The final stretch. RLHF, DPO, or whatever alignment technique you prefer—but now with full 1M context capability. This is where you teach the model to actually be useful with that massive context window, not just memorize it.

The Parallelism Switch: DDP → ZeRO-3

Here's the thing nobody tells you: you don't need ZeRO-3 or FSDP for everything. Phases 1 and 2 run perfectly fine with vanilla DDP (Distributed Data Parallel). Your gradients fit in memory, your model weights fit on each GPU, life is good.

But the moment you hit Phase 3 with 512K context? Your activation memory goes through the roof. An 8B model at 512K context needs something like 100GB+ just for activations. That's when you switch to ZeRO-3 or FSDP—shard the optimizer states, shard the gradients, shard the parameters, and pray to the NCCL gods.

60-70% of your training time (Phases 1-2) needs only DDP and 100Gbps networking is plenty. The remaining 30-40% (Phases 3-4) needs ZeRO-3/FSDP and benefits from faster interconnect. Don't overbuy networking for the phases where you won't use it.

Our Networking Setup: SN3700 from Day One

We bought a Mellanox SN3700 (32×200GbE) switch before we even had the DGX Sparks. Some might call that overkill for machines limited to ~100Gbps per link. We call it future-proofing.

The SN3700 gives us headroom. When Phase 3 long-context training demands more bandwidth for ZeRO-3 all-reduce operations, we're not scrambling for a switch upgrade. When we add more DGX Sparks (or eventually actual B200 nodes), the fabric is already there.

For Phases 1-2 with DDP on 4-8 nodes, you could get away with a cheap 100G switch. But if you're doing any long-context training (Phase 3+), the SN3700's 12.8 Tbps switching capacity and sub-microsecond latency actually matters. Plus, RoCE needs good switches—cheap ones drop packets under load and your training just hangs.

Realistic Timeline: 8B Model, 150B Tokens

Let's do some napkin math for training one of our 8B SLM ensemble members from scratch. 150B tokens total, curriculum learning, 20+ DGX Spark units in BF16.

Note: These numbers assume BF16 training on DGX Spark. On rented B200 with NVFP4, you'd cut this roughly in half—but at $4/GPU-hour instead of ~$0.08/GPU-hour (amortized DGX Spark cost). The math works out to doing Phases 1-2 locally and renting cloud for Phases 3-4 when bandwidth matters more.

The beautiful thing about curriculum learning is it's not just faster—it produces better models. A model that learned short context first and extended later actually understands context, rather than just being trained on long sequences and hoping for the best. NVIDIA figured this out with Nemotron, we just applied it to our C++ specialists.

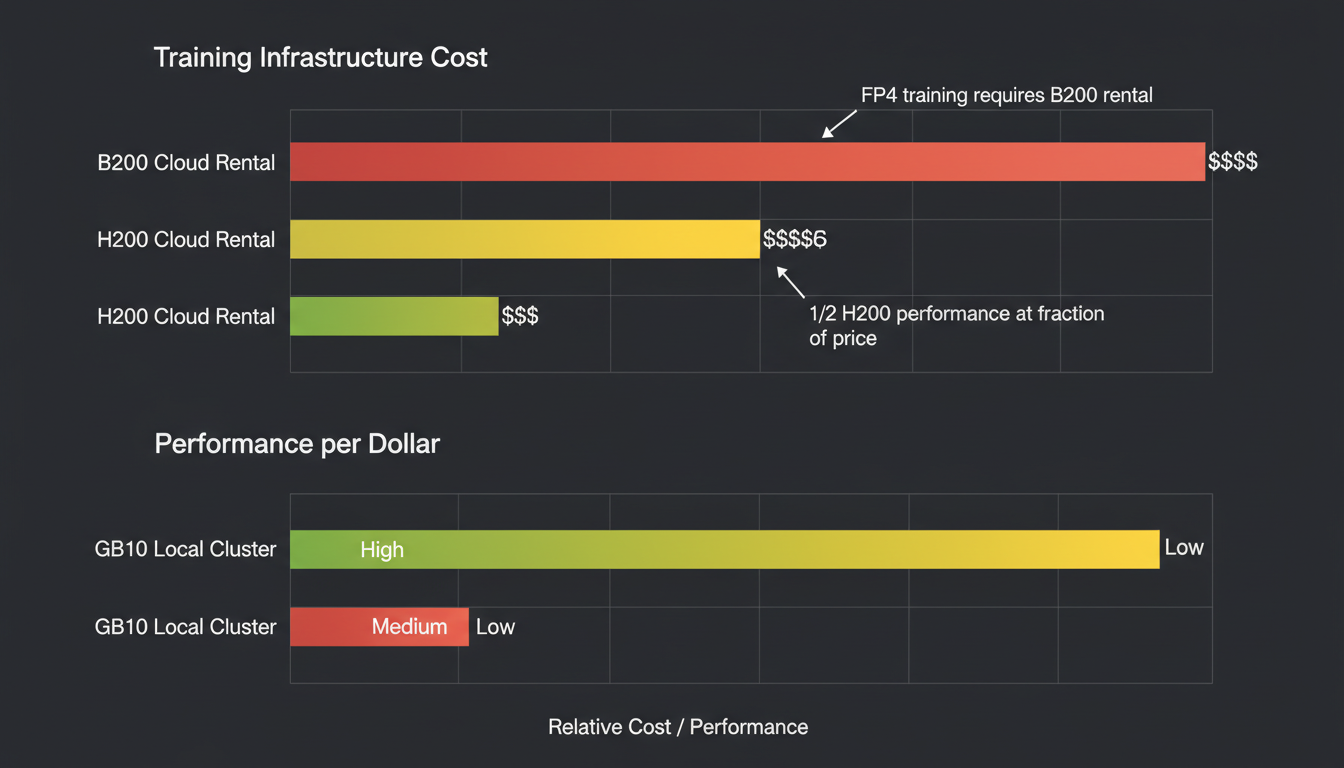

The Economics: Why This Makes Sense

Total cost of ownership: DGX Spark cluster vs cloud-only

Let's talk money—but let's be fair about it. A 20-node DGX Spark cluster costs ~$80,000 up-front. The key insight: GB10 delivers roughly 1/2 the BF16 performance of an H200, with similar memory (128GB vs 141GB), at 1/8 the price. That's the math that matters.

The Performance-Per-Dollar Math

- Price: ~$4,000

- Memory: 128GB unified

- BF16 Performance: ~0.5× H200

- Perf-per-dollar: 4× H200

- Price: ~$30,000+ or $3-4/hr cloud

- Memory: 141GB HBM3e

- BF16 Performance: 1×

- Perf-per-dollar: baseline

Translation: 2× GB10 units ≈ 1× H200 performance, but cost ~$8K vs ~$30K. Our 20+ GB10 cluster delivers ~10× H200-equivalent performance.

Monthly Cost: Performance-Equivalent Comparison

Our hybrid approach: Run all experimentation on DGX Spark (~$2,700/mo), rent H200/B200 for 100 hours/month for production NVFP4 runs (~$350/mo). Total: ~$3,050/mo for 10× H200-equivalent compute.

Breakeven vs all-cloud: ~3 months. After that, you're saving $22K+/month.

The key insight: you don't need datacenter hardware for prototyping. 128GB of unified memory handles most experiments. You only need B200-tier hardware for the final production training runs where memory bandwidth and NVFP4 support matter.

Lessons Learned

Forget raw FLOPS comparisons. The 128GB unified memory pool is why GB10 punches above its weight class. No PCIe bottleneck, no model sharding for models under 200B.

The Grace ARM CPU isn't an afterthought. Those 20 cores handle data preprocessing while the Blackwell GPU trains. No more CPU bottlenecks on tokenization.

5.91" × 5.91" × 1.99". 240W system power. Quieter than a gaming PC—runs perfectly in a regular office, no datacenter required. We have 20+ units across our server room and individual researcher desks. No booking compute time, no SSH latency, just run your code. We don't care about datacenter energy efficiency because we're not in a datacenter.

NVIDIA's custom Ubuntu comes with everything pre-configured: CUDA, cuDNN, PyTorch, TensorRT. Zero driver debugging. It just works.

Running 24/7 on cloud GPUs is financial suicide for a startup. Use owned hardware for the 90% of work that's experimentation, cloud for the 10% that needs scale.

GB10's SM 121 compute capability doesn't support NVFP4/MXFP8 training in Transformer Engine yet. RTX 5090 (SM 120) has the same limitation. Only B200 (SM 100) supports NVFP4 training. We're considering porting the kernels ourselves—it's that frustrating.

The Real Takeaway

The GB10 / DGX Spark is the first "desktop AI supercomputer" that actually deserves the name. 128GB unified LPDDR5X, 1 PFLOP of FP4 performance, 20 ARM cores, NVLink-C2C coherent memory—all in a package you can pick up with one hand.

For training 4B-8B parameter models like our SLM ensemble, it's the sweet spot. Enough memory for realistic experiments, enough compute for reasonable iteration speed, and a price point that makes financial sense for a small team.

If you're building specialized language models, stop paying cloud rental on experiments. Get a few DGX Sparks, reserve the cloud for production runs, and watch your runway extend by months.

Want to talk about training infrastructure?

We're happy to share war stories about GB10 clusters, SLM training, and the economics of AI development at startup scale.