A Million Steps Without Falling: What We Learned About AI Agent Orchestration

An agent that makes a 0.1% error rate sounds great until step 1000 when you realize you're debugging garbage.

The Catastrophic Math of Error Accumulation

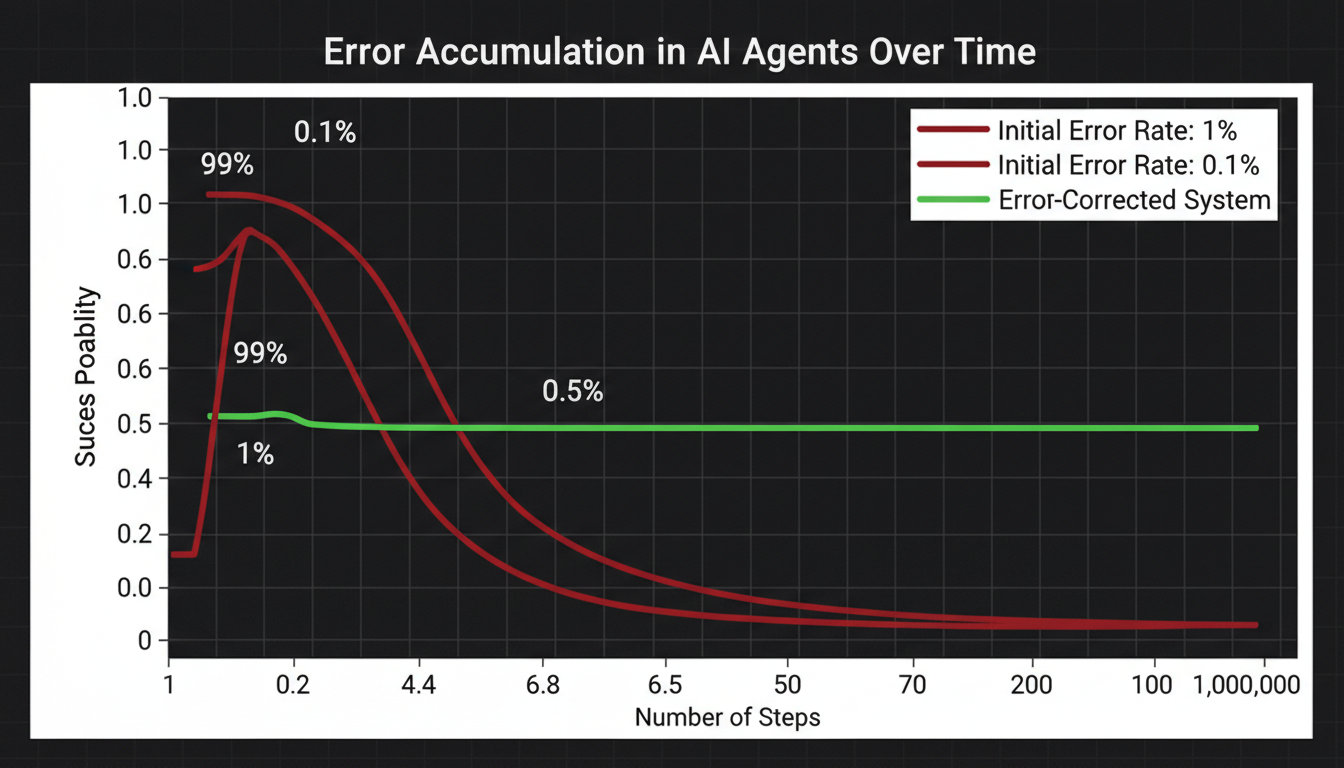

Here's the thing nobody tells you when you're building your first AI agent system: exponentials are brutal. Like, really brutal.

You've got an LLM with a 99% success rate on individual tasks. That sounds amazing, right? You deploy it, pat yourself on the back, maybe tweet about it. Then reality hits. After 100 steps, your success probability is 0.99^100 ≈ 37%. After 1,000 steps? 0.004%. That's not a system—that's a random walk toward failure.

Recent research from Cognizant AI Lab demonstrated something remarkable: they solved a task requiring over one million LLM steps with zero errors. Not 99.9% accuracy. Zero. Zilch. Perfect execution from start to finish. How? Not by making the LLM smarter, but by decomposing the problem into the smallest possible pieces and voting on every single step.

The Coordination Paradox

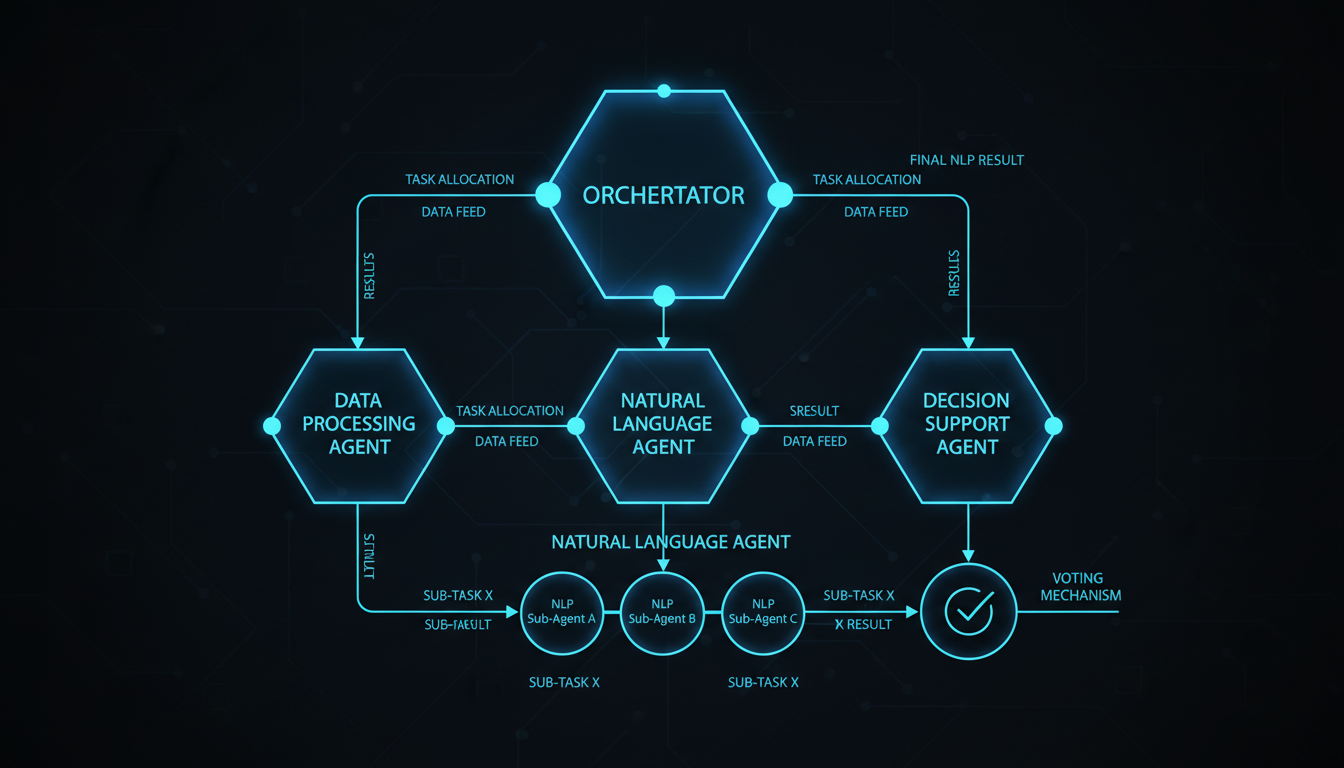

Here's where things get philosophical. Google's recent agent systems research uncovered something fascinating: sometimes adding more agents makes things worse. Not a little worse—like 70% worse.

The pattern is clear in their data:

- Financial reasoning tasks: Multi-agent systems crushed it—up to 81% improvement with centralized coordination. Why? The task naturally decomposes into parallel subtasks (revenue analysis, cost structures, market comparisons).

- Sequential planning tasks: Every multi-agent variant degraded performance by 39-70%. Why? Each step depends on the previous state. Coordination overhead fragments reasoning capacity.

- Tool-heavy tasks: The more tools you add, the worse multi-agent systems perform (β = -0.330, p < 0.001). Fixed computational budgets split across agents mean each has insufficient capacity for complex tool orchestration.

The insight: it's not about the number of agents. It's about architecture-task alignment. Independent agents amplify errors 17.2× through unchecked propagation. Centralized coordination contains this to 4.4× via validation bottlenecks.

Memory: The Cognitive Bottleneck

Let's talk about memory, because this is where most agent systems go to die. Not with a bang, but with a slow, context-window-exceeding whimper.

The recent memory survey from NUS/Fudan/Peking/MIT/Oxford reveals three fundamental memory types that agents need:

- Factual Memory: Knowledge from interactions. "User prefers tabs over spaces," "The production database uses UTF-8 encoding." This is your long-term knowledge base.

- Experiential Memory: What worked and what didn't. "Binary search on sorted inverted lists is 3x faster than linear scan," "Memory corruption in TBB pipeline happens when parent class methods are called directly." This is how agents learn.

- Working Memory: Temporary workspace for the current task. "I'm on step 479,806 of 1,048,575," "The last move was disk 3 from peg 1 to peg 2." This is where context compression becomes critical.

The brutal reality: these memory systems can be organized as flat structures (1D), graphs (2D), or hierarchical pyramids (3D). Each has trade-offs. Flat memory is simple but slow to search. Graph memory enables multi-hop reasoning but requires sophisticated retrieval. Hierarchical memory compresses well but risks information loss.

Our experience with FAISS Extended showed this viscerally. We had agents running benchmarks with 5×1GB batches. Without proper working memory management, context windows exploded. With compression? Clean execution, but we had to carefully balance what to keep (state information, error patterns) versus what to discard (verbose tool outputs, intermediate calculations).

Self-Correction: Red Flags and Voting

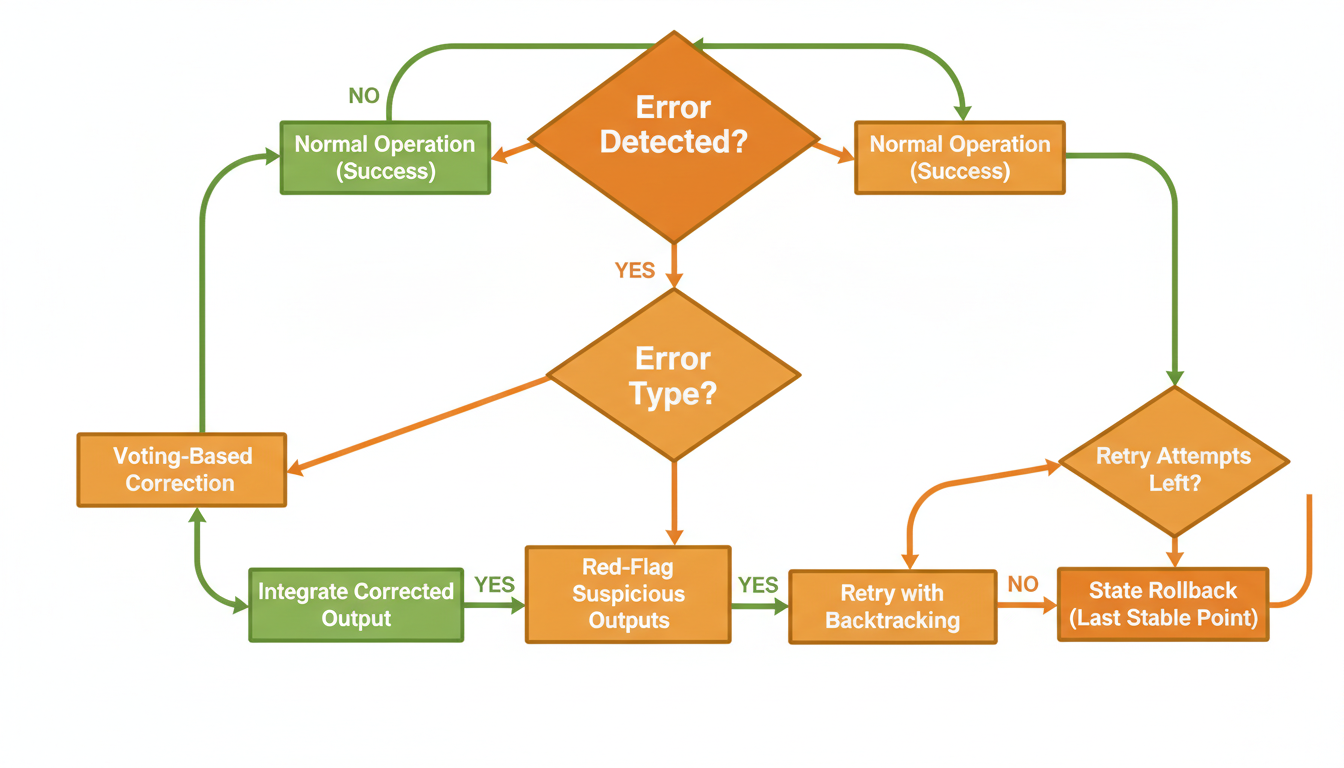

The MAKER system (Maximal Agentic decomposition, first-to-ahead-by-K Error correction, Red-flagging) introduced two brilliant ideas that we've adopted in our C++ code generation agents:

1. Red-flagging suspicious outputs: If an LLM produces an overly long response (>750 tokens when the task needs 200), something went wrong. If it can't format its output correctly, its reasoning is probably confused too. Don't try to fix it—discard it and resample. This simple heuristic reduced correlated errors dramatically.

2. First-to-ahead-by-k voting: Instead of simple majority voting, keep sampling until one answer gets k votes more than any competitor. This is optimal in sequential probability ratio tests and scales logarithmically with task size. For a million-step task, k=3 is often sufficient if per-step accuracy is >99.5%.

The math is beautiful: expected cost grows as Θ(s ln s) with maximal decomposition, versus exponential growth with larger subtasks. Log-linear scaling means you can actually deploy these systems in production.

The Compute Cost Reality Check

Let's talk about the elephant in the room: cost. The MAKER team spent about $3,500 to solve their million-step task with GPT-4o-mini (using low temperature and red-flagging). With gpt-4o-nano it would have been $41,900. With o3-mini, $9,400.

The counterintuitive insight: smaller, non-reasoning models often work better for long-range tasks. Not because they're smarter, but because:

- They're cheaper per token, so you can afford more voting rounds

- Their errors tend to be more random (less correlated), making voting more effective

- For focused micro-tasks, reasoning overhead is unnecessary

Our SLM Ensemble approach follows this philosophy: 7B-13B specialists, each focused on a narrow domain (C++ tokenization, template metaprogramming, memory debugging), orchestrated by a lightweight coordinator. Total cost per query? About 1/5 of a comparable o1 call, with better accuracy on our specific tasks.

What We're Building: C++ Code Generation at Scale

Our agent system for C++ code generation synthesizes these insights:

- Extreme decomposition: Break code generation into minimal subtasks (tokenization → parsing → semantic analysis → code generation → verification). Each agent handles one focused step.

- Hierarchical memory: Working memory for current context (function signature, local variables), experiential memory for what patterns worked (optimal SIMD implementations, TBB pipeline structures), factual memory for project knowledge (coding conventions, build system quirks).

- Centralized orchestration for decomposable tasks, single-agent for sequential: Parallel implementation of independent methods gets multi-agent treatment. Sequential refactoring? Single agent with strong working memory.

- Red-flagging everywhere: Overly verbose explanations, malformed code, invalid syntax—all get discarded and resampled. Costs more upfront but prevents catastrophic failures downstream.

- Integration with ground truth: gdb integration for actual execution traces, rr for time-travel debugging, FAISS Extended for semantic code search. Less hallucination, more verification.

The Real Lesson

The future of AI agents isn't about summoning ever-more-powerful LLM ghosts and hoping they get it right. It's about:

- Extreme decomposition (maximal modularity)

- Continuous error correction (voting, red-flagging, verification)

- Smart memory management (hierarchical, compressed, retrievable)

- Architecture-task alignment (not all tasks benefit from coordination)

- Cost-aware orchestration (smaller models, more voting, log-linear scaling)

An agent that makes 0.1% errors sounds great until you need it to run for 1,000 steps without supervision. Then you realize the math doesn't work. But with proper orchestration, memory management, and error correction? Suddenly a million steps becomes achievable.

We're still early. But the path is clear: treat LLMs like unreliable components in a distributed system, not as oracles. Design for failure, vote like your deployment depends on it (because it does), and never trust a response that took 2,000 tokens to say what should fit in 200.

Interested in how we apply these principles to C++ engineering?

Check out our FAISS Extended project (3-5x faster search with sorted inverted lists) or SLM Ensemble (specialized 7B-13B models that understand C++ semantics).

References

- Meyerson et al. (2025). "Solving a Million-Step LLM Task with Zero Errors." arXiv:2511.09030

- Kim et al. (2025). "Towards a Science of Scaling Agent Systems." arXiv:2512.08296

- Hu et al. (2025). "Memory in the Age of AI Agents: A Survey." arXiv:2512.13564